As the banks move to sort out their bad debts, it’s imperative that the state also tries to alleviate negative equity problem facing young workers.

As the banks move to sort out their bad debts, it’s imperative that the state also tries to alleviate negative equity problem facing young workers.

Just in time, the cavalry have arrived. On Friday, it emerged that some US-based private equity funds are interested in buying some of our banking assets. Bank of Ireland issued a statement suggesting that it had been approached and the state breathed a sigh of relief.

The first part of Brian Lenihan’s plan seemed to be beginning to work. The Minister for Finance gambled that if he waited long enough, some buyer would emerge because bank share prices would fall to such a low level.

Realising that he would have to write a cheque at some stage, Lenihan, by playing awaiting game, could at least avoid making the same mistake as Gordon Brown, who obviously bought stakes in the British banks too early and has lost a fortune of taxpayers’ money as a result.

Lenihan wanted to ensure Irish bank shareholders – not the Irish state – were exposed to the dramatic falls in share prices of the past few weeks. His judgment here was spot on.

Now that share prices are in cent – or as close to it as makes no difference – the state can begin to move, knowing that the downside is minimal. In fact, it might be well advised to wait a little longer before committing cash, because the banks might get even cheaper.

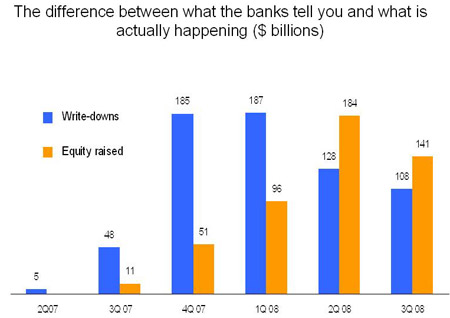

If you want to understand why banks might get even cheaper, look at the accompanying chart. This tells the story of the US banking system in the past year. It shows that banks are invariably always wrong when it comes to bad loans, because they underestimate the difficulties in their loan books. As you can see, the difference between the banks’ forecasts and reality was enormous.

When the banks realised that something was wrong, they went out and raised equity to cover the losses. To see the disparity between hope and reality, take the example of 2007.

In the second quarter of 2007, US banks realised that there was a bad debt problem of $5 billion. So, in the third quarter, they went out and raised $11 billion to cover these losses, believing that by raising $11 billion they would more than cover themselves for even a doubling of the bad debts from second to third quarter. But bad debts not only doubled, they increased by a factor of ten to $48 billion. In the fourth quarter, bad debts increased again to a whopping $184billion.

This chart is telling you that, whatever the banks are saying now, you can be sure that the problem will be much, much worse. Whatever the PricewaterhouseCoopers report is saying, a prudent investor can be safe to assume that the bad debts in Ireland over the course of the recession will be much worse.

Therefore, there is a huge risk in putting money in now because we have no idea what the true picture will be in a year. If you doubt this, just look at what happened to one of the savviest investors in the world, David Bonderman, the chairman of Ryanair. Bonderman put $7 billion into Washington Mutual last March, because he thought that the bank’s share price had fallen too far and it must be a bargain. By September, Washington Mutual was bankrupt and Bonderman lost all of his $7 billion.

Let this be a cautionary lesson to people who are committing money today – the minister included. The state will have to put money into this recapitalisation to match the private cash.

However, the question remains: what are we buying? For example, if the bad debts are admitted now by the banks to be €7 billion, recent history suggests they are likely to be three times that at least, meaning that the bailout will have to have a warchest of over €20 billion to succeed.

To raise that type of money, Lenihan will need to return to the idea of ‘war bonds’ where he opens up the recapitalisation to the Irish people, so that we can all participate in the upside as the economy recovers. But the recovery won’t come on its own. While numbers like €20 billion are extraordinary, we are living in extraordinary times, which call for extraordinary measures.

One extraordinary measure that has to be considered by the minister as part of any restructuring of the banking system has to be some alleviation of the negative equity problem faced by hundreds of thousands of young people.

Many people would see such an initiative as heresy, as it rewards the bad behaviour of those silly enough to scramble into a housing loan when prices were at their most ludicrous. A large part of me agrees with this, but for future social cohesion we cannot tolerate thousands of young people (in many cases, young families) defaulting on their mortgages and being kicked out of their houses. Neither can we entertain the prospects of those people languishing in negative equity for a decade.

Make no mistake about it: Ireland is likely to see massive mortgage defaults in the years ahead. The reason is simple: unemployment is rising rapidly and will be in double-digit figures by the end of 2009 or early 2010. Many people who lose their jobs will not be able to pay and the banks face a choice, either take the houses back or renegotiate the mortgage.

Instead of waiting for that in an ad hoc way, why not now, as part of the restructuring of the banking system, reset the principal of these mortgages down to, let’s say 50 per cent, of their peak value? The banks’ shareholders would take on the lion’s share of this pain, with the state taking a proportion.

But such debt forgiveness doesn’t mean the lender is off the hook. They pay later. As people move houses over their lifetimes and tend to trade up, the capital gain when the mortgage holder sells on the starter home to the next generation goes to the state.

Therefore, the state is protected, the system is preserved, the banks take the hit and the mortgage holder keeps his house today at the price of significantly lower capital gain tomorrow. It is a bitter pill for the banks to swallow, but so be it. Better to have someone paying some interest on a smaller amount of principal than paying nothing on a big loan.

The other main reason negative equity has to be addressed is that people with negative equity will not spend no matter how well the banks are capitalised. Without spending, the recession gets worse, unemployment rises further, tax revenues fall further and the negative cycle perpetuates itself.

Equally, what reason is there to stay in Ireland if you lose your job and your home? This is a possible future for an entire generation. The property boom enriched the middle-aged and indebted the young in a ‘generational scam’, which is now becoming increasingly evident. Without some really imaginative thinking from our politicians, this generation will move away from Ireland and mass emigration and social unrest is a likely prospect.

Therefore, a move to alleviate negative equity for our young workers is not only advisable, it is imperative. The banking crisis and its subsequent restructuring, gives us the opportunity to sort this out. No matter who eventually owns the banks, this is going to be a cost. This idea might not be for the financial purists, but it is for the social realists, and facing up to reality is what recessions are all about.

[23/11/2008, 11:40am]: chart added

David I hear what you are saying about the negative equity reduction scheme. Your heart is in the right place. I agree with you on many levels. However, this will turn into a free for all. Just look at Washington now with the bailouts. Dutch companies are buying US Banks to get in on the bailout bonanza. Detroit is trying to get in on the act. (GMAC is now a bank it seems!) If they do something like this it will need to be very carefully designed, crafted and audited by very honest non political brokers. This is a very… Read more »

THE GOOD OLD DAYS ARE GONE. Yes indeed it’s time to pay the piper with whatever you can. Let the home owner negotiate an interim differential rent until the borrower can bail himself out of renting what he owns. It will be a more punitive measure for the buyer, and it would pump real money into the system. It’s not easy to forget what you are owed, but if you have someone giving you disposable cash every week you could at least generate a cautious (if there is any such thing, ha) business into a big business in these bad… Read more »

Alternatively David, in many cases people could trade down to decrease their liabilities and start afresh. This is a viable option for very many people, except those in the lowest rung of housing, who bought at the peak of the boom. But of course people don’t want to cut their cloth to fit, and apologists like yourself are pandering to them. Your assertion that people with families will be ‘kicked out of their houses’ is sensationalist ; despite the ridiculous over-pricing of the recent boom, there is a large variety of housing categories available to trade up and down to.… Read more »

Where is the chart?

i can’t believe David you are still pushing this notion that the poor first time buyers should be bailed out. Did you ignore all the comments made by your readers last week? The idea that hard working taxpayers funds will be used to bail out the most reckless, foolhardy eejits ever born in this country at a time of health, infrastructure & education cuts is incredulous. At most, if anything is to be done, there could be a roll-up of interest for people who lose their jobs (similiar to what is proposed in the US), but the debt would have… Read more »

Ireland 2030.

“Daddy, I’m not sure if I can afford that 10x salary multiple for a shoebox in Tyrrelstown.”

“Now Johnny, let me tell you a story from when I was young.

I couldn’t pay my mortgage, but the government just wrote it off for me. They said it was a one-off but that’s just them talking.

If the shoebox goes up in value you get a huge profit, if it drops in value just get the government to write off your mortgage. You’ll be fine.”

David – GIVE ME A BREAK

Banking buy outs or recapitalization or whatever phraseology one uses are inevitable. My concerns are about the WHO and the nuts and bolts of these deals. Regulation is one of the most important factors to prevent the Poker playing mentality getting a free fall foot in the door. Brown may have gambled too early but he was coming at least from the right place in my view. The Irish Privatisation agenda has screwed up big time. Government needs to be extremely careful in how they do business on behalf of us the taxpayers. Nationalising banks in part needs to happen… Read more »

Whether or not all or any of the propositions in the article are palatable or not, at least it’s strategic thinking. I fully agree that we can’t allow another “brain drain” which has already started. The people who were duped this time should be shown some degree of mercy by those who were duped the last time. You cannot put an old head on young shoulders. Since money has lost all sense of proportion and reality insofar as we’re now talking in Trillions (what comes after a trillion?) and the banking fraternity were the custodians of that reality, we should… Read more »

[…] the Irish gov bail out first time buyers? David McWilliams appears to be advocating it in his article today. I have to say that, even though I am one of those […]

Like some of the other comments, especially ‘Paddy the Pig’, I think this article’s proposal is ridiculous. Do we reimburse people who make unwise investments in the stock market too? I wouldn’t mind having all of my investments turn to green again please. No, unfortunately I’ve had to suck it up and play the waiting game. Instead of re-valuation of mortgages, why not come up with a smarter solution which would be involve letting them walk away from their mortgages easier? This could work a number of ways, either a one-off amnesty for people to simply turn in their keys… Read more »

There is a serious possibility that the youngest and brightest people in the country will not be sticking around and Ireland will be seeing an exodus of potential. One of the reasons for this is that the majority of smart people who came from university over the past 5 or 6 years, people with the ability to innovate, didn’t buy into the housing bubble knowing full well that the prices were in outer space. Now they find themselves in a country with little opportunity in front of them and nothing to keep them here.

David. You’re pretty determined with this one! You are putting forward two arguments in favour of the FTB bail-out. Firstly, you say ” people with negative equity will not spend no matter how well the banks are capitalised. Without spending, the recession gets worse, unemployment rises further, tax revenues fall further and the negative cycle perpetuates itself.” This seems by itself to be a good argument. But. You suggest that the bail-out be funded by ‘War-Bonds’ paid for the Irish people. So the demand increase provided by the relief given to FTBs will be matched by a demand reduction from… Read more »

Which would do more to prevent a brain drain – lowering taxes for start-up business, providing R&D grants, giving export assistance, lowering income taxes OR giving taxpayers money to the few who borrowed recklessly? I don’t know how you think the banks have the billions to spare for this, or that their shareholders would suffer it. Can you please refrain from calling it a whole generation of people in negative equity. I am a member of that generation and will happily continue renting for the next 2/3 years, as will plenty of others that I know. Many of those who… Read more »

Furrylugs – quadrillion comes after a trillion I believe. I’m sure it won’t be long before debt in the States reaches quadrillions.

I think that this debate is at least five if not ten years too late. We are tilting at windmills here and we are only looking at the consequences and not the causes of the current difficult situation. We had and still have a housing mania that was fuelled by government bodging and a credit market that had the safety catch off. I worry when the bank wants to give me money not when they don’t. It still amazes me that we have the same thicks that overheated the housing market still in charge and the banks and developers still… Read more »

I’ve enjoyed reading David’s articles and the comments here now for a while,this is the first time I’ve felt the need to comment myself though. This idea of debt forgiveness is nonsense in my opinion,you make your bed and ly in it.Every chancer in the country would be looking to get in on it,depending on who you know and what strings could be pulled.If people were stupid enough to sign up to mortgages they couldn’t afford then they have to live with the consequences of their own actions,I couldn’t see the prople of Ireland standing for any such sheme.I certainly… Read more »

Before the bubble burst , the prevailing mentality was one of “Me first, I’m alright Jack”. I see no indication that that mentality has changed now, Debt forgiveness in reality would amount to people taking advantage of the situation to improve their own lot at the expense of others. Indeed, it is strange that David is championing this course of action, since this is the very essense of “privatising profits and socialising losses” which he warned should not be tolerated only weeks ago. For the long-time financial and moral health of the country, it is important that difficult and painful… Read more »

David assumes the Government will be in a position to decide the best sociable solution to our national problem…..I have my doubts …..if they ever will be able …..my experience with high class financiers is that they seek their full pound of flesh after paying their dig out commision to a derailed politician and ‘ secure it ‘ with cheap money from a dubious source conditional that the financiers make a profit before they actually pay anything and the loss of face value is left ( which will be far less than the profit made by the financiers ) to… Read more »

David headlines: “Its time to face up to reality” Okay, much of the discussion so far seems a bit panic-stricken, so perhaps a few facts will draw it back to equilibrium: The average house price, new and second-hand, in Ireland in September 2008 was about €270,000. According to the 2006 census there were about 1,500,000 houses in the entire country. So the total value of housing in the state is about €400 billions. Less than €50 billions of this is mortgaged (somebody out there might have a better total). So even if 10% of mortgages default the total exposure is… Read more »

I made comments on this last week too. Almost everyone here agrees that baling out the FTB is a bad idea. Elements of moral hazard, effectively punishing those who were too smart to buy into the hype or too poor to able to reach the bottom rung of the ladder as well as the very questionable rate of return for society on an investment in the reckless and stupid all add up to solid reasons not to bale them out. The argument that these people will contribute to the economy is weak. If they emigrate, well, they weren’t the most… Read more »

I am wondering if this plan is already in place. Maybe this is part of Cowen’s great plan to get the economy going as described in the irish media the past week.

David successfully “predicted” the bank guarantee. Maybe this is a “prediction” too? Am I too cynical?

Ger

I am an IT graduate with in my mid 20’s working for a successful and innovative Irish owned R&D company. if I ever see such a scheme as David suggests implemented, I would pack my bags and head to OZ, or indeed any other country without such widespread social corruption. I wouldn’t be able to live with the resentment of the fact that hundreds of thousands of people older than me are rewarded for unwise investments. In the interests of fairness, the system should be allowed to equalise itself and the same set of rules should apply to everyone, because… Read more »

Evening all, David here. I’m listening to your responses and it seems that almost unanimously any idea that alleviates the pain of our FTB generation is regarded as extremely silly. This is the position I have always advocated, and have taken a bit of flak by being unforgiving in applying economics, not politics to the analysis. But I’m beginning to change my mind. Up until very recently, I regarded any slump in prices as a cleansing of bad behaviour, leaving us better off on the far side. Now I am starting to think that as we are not in a… Read more »

David, To my mind it’s natural to vent ones feelings against the perceived perpetrators of this mess. This is a systemic global failure which our myopic, greedy bankers got sucked into. Similarly shareholders who demanded more and more profit. Our rulers codded themselves that they were responsible for the “wealth” and have only now become aware, in horror, of the fundamentals of a bubble in economic terms. I can’t blame young FTB’s for wanting to own their own house and better themselves. They were actively encouraged to by society.Neither can I blame someone for wanting a second house for the… Read more »

” almost unanimously any idea that alleviates the pain of our FTB generation is regarded as extremely silly”

Who’s that banging on the door Dougal?

It’s Moral Hazard Ted

Ah shure tell him to come in and we’ll give him a nice cup of tea. Mrs Doyle !!

David wrote: “However, the question remains: what are we buying? For example, if the bad debts are admitted now by the banks to be €7 billion, recent history suggests they are likely to be three times that at least, meaning that the bailout will have to have a war chest of over €20 billion to succeed.” Sounds right. If so, what benefit a few billion from both the government and the private capital vultures circling the wagons at present.? Only serious money wil begin to address this debacle. I- like thousands of others- lost a lot of money on irish… Read more »

Ok, so you ‘ring-fence’ the original mortgage debt. But won’t that only bring more egregious issues to the surface? What about the car loans? The credit cards? The ‘home equity loan’ that was drawn down to pay the creche fees – “because in 3 years we’ll both be earning so much more and ready to trade up to a much better place“? The store cards which I never told you about? That building plot in Croatia? All of which are probably secured against the property. Even if there’s any way of tweaking the tax system to allow an ‘imputed’ rental… Read more »

There has go to be a better solution than this. There are two issues here: First of all we’ve got a great mass of people who’re going to be less use to the economy than they might, if this plan doesn’t go through. They’re going to be weighed down with debt, not spending, etc etc. Secondly, we have the law of unintended consequences. What will they be for bailing out those in negative equity (what about the STB’ers?). There will be unintended consequences. There most assuredly will. If ever there was a time when Mr LookBehindYou, with impressive lungs, was… Read more »

On second thoughts, the wealth tax wouldn’t exclude Stock Market Investments or Government Bpnds.

This tax would be a replacement for David’s War Bonds. Very little real wealth has been created, it’s just been moved around, ending up in the laps of a few rich people. It’s time to think of the country as a whole, and rather than charge the little guy for this nonsense, we should just accept that it’s all been a frightful cock-up, and get those whose laps the money landed in, to pay for it.

I invested a large part of my life savings in Bank of Ireland shares and have watched the share price fall from €18 to €1.

As a shareholder can I take a legal case against each individual of the board of management for negligence?

Rather than throw good money after bad would it not make more sense to set up fully state owned banks from scratch (like ICC and ACC) with a mandate to lend to FTB’s and businesses in a sensible way. This would open up the credit to these important sectors of the economy. The national pension reserve fund can be used to invest in this and would receive a rate of return. If the government does decide to invest/ recapitalise the banks they should insist that non performing loans are identified and acted upon quickly. The fact that interest roll up’s… Read more »

David, agree it’s “time to face up to reality”. The problem is I don’t think our political leaders understand the reality , therefore they are signing us all up to trouble in the future with a weakended position of control over the sector. I think you may be giving Minister Lenihan too much credit for his judgement on waiting for a buyer to emerge if the price was low enough. The reality is as soon as the guarantee was announced there have been financial ‘sharks’ in Dublin city working on a plan to attract private equity investment to buy out… Read more »

At the risk of incurring the wrath of the webmaster, I publish here Article 45 of our Constitution. it’s supposed to be the means by which we control, for the common good, the society we live in. DIRECTIVE PRINCIPLES OF SOCIAL POLICY Article 45 1. The State shall strive to promote the welfare of the whole people by securing and protecting as effectively as it may a social order in which justice and charity shall inform all the institutions of the national life. 2. The State shall, in particular, direct its policy towards securing: i. That the citizens (all of… Read more »

Oh yes, as regards penalising our OAPs and Kids………….

4. 1° The State pledges itself to safeguard with especial care the economic interests of the weaker sections of the community, and, where necessary, to contribute to the support of the infirm, the widow, the orphan, and the aged.

2° The State shall endeavour to ensure that the strength and health of workers, men and women, and the tender age of children shall not be abused and that citizens shall not be forced by economic necessity to enter avocations unsuited to their sex, age or strength.

What really needs to happen and as quickly as possible is a “floor” to be found we have entered the negative spiral which is a self fulfilling loop. I commend the brits for trying the VAT stimulus measure slashing it to 15% when we increase ours to 21.5% This is a brave step and just shows how government can take action. What big steps can we take to show we are willing to tackle the problem ? AS the property market has completely stalled and this caused the bulk of our current problems. What steps can be taken to remedy… Read more »

I daresay a VAT rate decrease is of little interest to somebody with no job and a 450k mortgage.

If you want Joe Soap to spend then work at helping businesses to keep Joe in employment.

Paddy the Pig here. Thanks Mugsy Thanks Ruairi Author: Mugsy Comment: “”””Like some of the other comments, especially ‘Paddy the Pig’, I think this article’s proposal is ridiculous.”””” Author: Ruairi Comment: paddy – “”””I am totally at a loss to understand how any trading up or down can occur in a frozen market. …………If you could elaborate on this though, I’d appreciate it. I don’t see how it works.””””” Ah if only I had a mathematical brain like Einstein. Turfing people out (whoever “those people” happen to be) means more debt; banks with empty property that could – and will… Read more »

Some people are impossible to please. I think it’s your choice of the phrase “war bonds”. If you’re talked about a “democratic recapitalisation” then we’d be all for it! Seriously though, I think this is a cracking idea if a little rough around the edges. A dual pronged approach with cash from the NPRF and some from “democratic recapitalisation bonds” could be the best approach. It’ll be a sop to the public sector bashing and if ever there was a rainy day for spending some of the NPRF money this is it. Your basic suggestion of passing the write-downs onto… Read more »

exactly Johnny… even better why not take the money allocated to the subprime business and invest it in the banks when they are desperate for cash and at terms where we can get a return. Whether someone owns or rents is not as important as whether they are are warm and dry or cold and hungry. The houses are already built, they will rent at their market rate. “time to face reality” The reality is there isn’t enough money to solve this problem for everyone…. we may have enough money to avoid bankrupt the country if we pay our cards… Read more »

so if the older generations have been enriched, let them be the ones to bail out the FTBs, indeed, perhaps by a selfless gesture leading to inheritance spending boom. Drink the Kool Aid old people. Drink it!

Hi David, > US banks realised that there was a bad debt problem of $5 billion. So, in the third quarter, they went out and raised $11 billion to cover these losses, believing that by raising $11 billion they would more than cover themselves for even a doubling of the bad debts from second to third quarter. But bad debts not only doubled, they increased by a factor of ten to $48 billion. In the fourth quarter, bad debts increased again to a whopping $184billion. Banks raising money has nothing to do with their predictability accuracy of bad debts. Bad… Read more »

“There is a serious possibility that the youngest and brightest people in the country will not be sticking around and Ireland will be seeing an exodus of potential.”

My friends left for Australia earlier in the year, they are now back in Ireland, as they could not find work.

As ever, the talent will emigrate and the shit will stay behind.

Both my friends who travelled to OZ are professionals, the doors are closing for everyone, and it has only started, wait until 2009 then the fun will really begin.

As for bailing out people in negative equity, they will turn around and stick two fingers up at the rest of us, while having a good laugh, that is a guarantee, because there is one thing the Irish are good at, and that is looking down on each other, and acting smug.

Lenin would have been a capitalist had he had a second life and who knows he may be reincarnated somewhere in Dublin. Leninhan….made his recent successful decision not that he was wise or that he had foresight ….he did so because he had the advantage of hindsight from mistakes made by gordon brown…so it was common knowledge …..we must not pour garlands on the incumbent minister …he has yet to show what he maybe capable of ….and my doubts are becomming greater as each day passes ….i do not expect the two b’s that are two lawyers talking convincing economics… Read more »

Just commenting on Davids followup “Now I am starting to think that as we are not in a recession, but something that may look like a deep, deep depression, the political upshot of the depression is social and political chaos. Being a natural evolutionary rather than revolutionary, this prospect scares me. As a result, I am prepared to entertain new ideas. In the 1970s inflation wiped out the debts of Ireland’s mortgages FTBers. As long as we are in EMU, this won’t happen. In contrast, we are now facing deflation and this means the incidence of debt is even higher.… Read more »

We have no food or fuel security. If it kicks off in the UK or in mainland Europe we will be sitting here in the dark with feck all to eat.

Its that serious.

b – thats the most rediculous contribution i have read to date…..our nation is endowed with all the riches of the land, sea and air ….unlike most of europe….our problem is that as a nation we suspiciously are more interested in philosophy than getting things done simply…this is our Atlantean thought process we aquired from our forebears …Phoenicians ……we need to reason more …and ……….NOW

There are two problems with the negative equity (FTB) bailout problem. 1. The moral hazard is certainly a big problem as it’ll result in FTBers making money at the expense of the tax payer. It’s also just plain unfair, unless the FTBers have to pay it back (over time). More importantly: 2. It just won’t work. It will not have the desired effect. We are acting as if we’re in a normal sort of ‘over-heating economy’ recession: Companies invest too much in people and productive capacity, produce to much. In this situation, you increase interest rates, and cause a recession… Read more »

[…] It worked well for the Nazis in the 1930s, and could work again here.” (Lorcon, commenting on David McWilliams’ site, 23 Nov. […]