This may seem like a distasteful question to pose on a Sunday morning, particularly if you are sitting across the kitchen table from someone you love, but I’ll ask it anyway: do you think divorces are good for the housing market?

Or, to put it another way, did you think that rising house process might allow people who have wanted to split ages ago to finally divorce? If you are happy together, maybe this question doesn’t apply to you, but think of others.

What if, far from being happy, you are reading the paper or your tablet, sipping a coffee and sitting across the kitchen table on this Sunday morning from someone you can’t stand, yet have not been able to leave because of the negative equity in the bloody house you both bought a month before your stupid, expensive, over-the-top Celtic tiger wedding with its personalised bloody menus?

That now seems years ago, doesn’t it? And indeed, the wedding was years ago, a bloody lifetime ago, and if it wasn’t for the fact that your stupid starter home collapsed in value, you’d have been out of there years ago.

But the house did collapse in value, and you had to continue servicing the mortgage, and obviously you couldn’t sell because this would have crystallised your losses! This would have meant that you would have been in debt as well as divorced.

Bad enough having made a fatal error marrying in the first place, but the idea that it would cost you to leave him/her was too much for you to bear. So you both stayed together, seething, hating the sight of each other.

This description of familial dysfunction may seem a bit far-fetched, but it isn’t.

Economic fortunes have a massive impact on stability and marriage. In Ireland, 2006 was ”peak wedding year. More people got married at the top of the boom than in any year since the foundation of the state.

Yet these marriages smashed straight into the wall of economic collapse, putting massive strain on relationships.

Still, the Irish divorce rate remained the lowest in Europe. There are only 0.7 divorces per thousand people in Ireland. Catholic Belgians are four times more likely to be divorced than we. French people three times more likely, the British a bit less so. Even in the reasonably observant Catholic Spaniards and Portuguese, divorce is three times more common than in Ireland.

This is at a time when all other indicators of social behaviour, such as the average age of marriage in Ireland (34 for men and 32 for women), is more or less consistent with the rest of the EU. So too is the average age of women having their first child, and anecdotal survey evidence about infidelity suggests we are no more and no less likely to ”play away as other Europeans.

So what explains the divorce anomaly?

Could it be that the fall in house prices (and therefore, wealth) locked people into bad marriages? If so, will the rise in house prices lead to a tsunami of divorces over the coming years?

And if this in turn is true, will divorce rather than new house-building ease the supply bottlenecks in the housing market? (After all, there has to be a silver lining for someone!)

Estate agents in Britain talk about the three Ds as being crucial to housing supply. They are debts, death and divorces. People’s houses are sold when they die; when they have to get cash in order to pay debt; and when they divorce.

If we are living longer (which we are), if the banks in Ireland are exercising forbearance (which they are), implying that people with huge debts have not been forced to sell, and if we aren’t divorcing (which is the case), the housing stock gets stuck and expected supply doesn’t come on stream. It seems fair to say that this is precisely what is happening in Ireland.

We are getting older and living longer. In fact, Irish men in particular are living longer today than at any stage in the history of males on our island. Also, because the banks put many people on interest only and didn’t want a deluge of debt-related sales, there are more people in houses now in default than would be the case in another country. And, finally, because negative equity has been so severe, people are having to stay together.

So what is going to happen now that house prices are rising rapidly, at least in Dublin?

All over the world, the emotional and mental strain placed upon marriages that have lost their spark takes a back seat when a household’s finances are in trouble. As asset prices, particularly property, plummet during recessions, the value of the family home of the once optimistic and bright-eyed couple gets hit hard.

This, coupled with falling wages, higher taxation, and in some cases redundancy, means that a divorce may not be financially viable for the struggling unhappy couple.

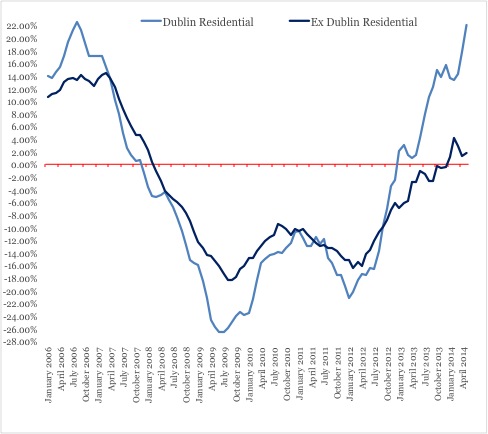

What about when things are looking up? As we can see from the chart below, residential property in Dublin has soared in price while the rest of the country lags behind.

But let’s go back to the three Ds. It is not likely that our lifespans will change greatly in the years ahead. But it is highly likely that people who were postponing selling the family home and staying together through gritted teeth will flog soon.

Some may hang on now for another year to get a better price. This might mean that they could actually get out of the marriage with a bit of cash, which would be a bonus. Others might think to themselves that, having stuck it out, they could do another year in emotional limbo if it meant getting a few quid. Others will have had enough.

In the months and years ahead, we should expect to see the Irish divorce rate move up to the European average as property prices rise. This is one of the unintended consequences of economic boom and bust – and now another house price rally.

Subscribe to receive my news and articles direct to your inbox

Subscribe.

Hi David, Very courageous article David. Great balls and backbone needed to produce it. The only economist I have come across who translates how the decisions taken by politicians etc affect real bread and butter issues for ordinary people. The MORE you ask questions like this the MORE you will be regarded as a real heavy weight commentator. Remember you will draw the ire of the politicians for vital commentary of this nature but that is something you should take enormous personal satisfaction from and indeed is a real badge of honour. Just under I’d say half the fellas in… Read more »

This is an interesting effect of the economic recovery which is gaining pace for sure. Very interesting to see it all around us. I was on the way back from an 6AM drop at the Airport in Dublin this morning when I came off the off ramp from the M50 there was a couple of construction lads waiting for a lift at the traffic light at the top………..haven’t seen that since 2007. Breakfast roll man is back in business…..!!! Currently I understand construction is about 5% of economy and a healthy level is 9%. I wonder how many jobs that… Read more »

Cheers Pat. That’s the type of anecdotal stuff that tells the story. best D

My house is just on the Meath side of the dublin-meath border. Remember I’m not actually in dublin, although I am closer to the city than many towns in dublin county (maybe that explains this). Anyway, just 6 months after I bought it, a similar house around the corner with a smaller garden sold for 20.3% more than I paid. So the irrational exuberance is back – and its not just for dubliners.

David and others – would you care to give your predictions as to when this boom will pop please?

If only it were possible to buy stock in David McWilliams himself :-(

Imagine the bubble that would grow there!

Frankie Boyle – interview on Scottish Independence generally, but expresses same view about ‘the property dream’ .. being trapped in a loveless marriage by negative equity. from 16.30 onwards Kaiser report last year. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3WAoMXHILts

“Irish men in particular are living longer today than at any stage in the history of males on our island.” Sadly I’ve experience of many couples trapped in the tragic situation David describes and I’d be surprised if any of the affected men see past their 60th birthday. Prolonged mortgage-recession-related stress levels will likely see a future spike in early deaths among the Irish male. The banks’ forbearance is doing most of these desperately unhappy families no favours. The extended Dublin commuter belt is particularly depressing when one factors in dislocation and isolation from their original family-community locales. A lot… Read more »

“What message will today’s children pick up in such an environment?” We need to tell them the truth as Sun Tzu said “if you know yourself and you know your enemy your victory is not in doubt” When the famine holocaust occurred in Ireland it happened at a time when we were still exporting food and the whole Island was owned by 750 people. They had a plan to reduce the population to 500k from 8m which suited their needs to convert Ireland from a landlord tenant system to one producing food for the UK mainland market. A million were… Read more »

I think we’re just catching up with other European Countries for divorce rates. A knock on effect if kids are involved will be social housing. We don’t live in Hollywood, few come out of divorce wealthy and the banks won’t be in lending mode to either party. That falls on the taxpayer in several ways and housing is one aspect. I think some have done a traditional Irish style divorce and bailed out of the Country. I wonder if that information can be gleaned from the emigration statistics?

I just don’t think divorce is very popular in Ireland full stop. It’s a small island country with strong family values. People tough it out.

I don’t think it is anything to do with house price.

Hi David, A very interesting article. Your articles really get me thinking about real life issues. I’m thinking about the question you raised when asking what causes the anomaly between divorce rates here and other countries of the EU. A look at divorce rates in Ireland show that the rate of increase in divorce is huge between 2002-2012. It still rose during the recession. I would hazard a guess that growth rates in Ireland are going through a type of Solow Growth convergence with the rest of the EU:) I agree that divorce rates will converge with the European average… Read more »

‘Till debt do us Part’ The above is the cover of the wrapper If I was kicking the ball this article is about : ‘ If I can divorce my spouse why cannot I also divorce the Bank Debt ‘. Unfortunately our Constitution by default will not allow that happen ….and the Electorate …will do nothing to change that . Thus the Vatican …correction …the DÁIL impose on all of us to remain as a union in financial misery …for worse and for worse until your death allows you to depart from ‘Your Debt’. Economics has nothing to do with… Read more »

Apparently Limerick Citay has the highest divorce rate in the country and some of the cheapest property prices in the country.

And up the road in Ennis, we had lyin eyes herself hiring an Egyptian to shoot dead the rich man with a large property portfolio who wouldn’t marry her….isn’t that right Michael Coughlan?

….heading for the cheatin’ side of town!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vzePxDeaucg

Societal Changes can prevent the norm that this article professes . As in the Arab world when a woman divorces her husband she is allowed to live in the extended family and share the spoils …..but then this was part of desert life at that time. And it was only Tents people slept in.

Lets buy sand and sleep on it.

I’ve been thinking about starting my own little multi-national tax cheating arrangement to launch a product I have nearly finished developing. So looking for a base outside the G20. Looking for ideas on where would be a good country to escape to when the shit hits the fan? Belize maybe?

very clever title David …i was sure it was an article on Argentina.. The “silver lining” of Messi’s genius to one side,the vulnerable Argentinean Republic face an enemy vulture fund whose evil brutality surpasses even that of ISIS.Empire’s genocidal bail-in strategy is now in full swing! Who is launching this morally bankrupt offensive on our Argentinean comrades? Why none other than evil-personified,billionaire Gollum-like-creature and war-monger Paul Singer of NML Securities(and others).This extortionist leads his vulture fund ‘hit-squad’ into war and the chosen enemy/prey [up until now] has been primarily the vulnerable sovereign nations of Africa. Argentina debt is 160% of… Read more »

It’s what my old dad used to say about the late 1910s – for the last 15 years, wherever you turn, it feels like warmongers on the rampage. What’s very weird though, is that, however bonkers they got, all the crazy haired conspiracy theorists have all turned out to be right. I guess it’s why there’s no effective satire – reality is more disfunctional than the Simpsons – much. I completely gave up the other month when it became apparent that the English State church having been lying like actors about their congregation numbers for 20 years, and their police… Read more »

Why are central banks buying up gold now?