If you want to understand the economic power of Germany, just drive here. You can feel the vibrations of this great superpower on the inside lane of the A1 autobahn from Dusseldorf to Cologne. Unlike motorways in other countries, which can be empty or when full are full of cars, the German motorways are unambiguously part of the industrial infrastructure. They are the manufacturing arteries of the economy and the inside lanes shudder with juggernauts moving goods in and out of this extraordinary trading phenomonen.

The trading success is nothing more than the amalgamation of the excellence of thousands of companies, employing millions of meticulous craftspeople, who through serious application to the business of commerce have made this country what it is.

Sitting in the dark paneled surroundings of the Hofbrauhaus Fruh in the shadow of Cologne cathedral, watching elderly Germans scoff down schnitzel and local red wine, it’s hard to imagine that this generation – Germany’s post-war greatest generation – could have, even in their wildest dreams, conceived of the success they have made of their national enterprise.

A few yards away, up and down the great Rhine, huge barges mirror the inside lane of the autobahn, ferrying manufactured goods up the river and out to the world via Rotterdam a few hundred miles upstream.

Unlike other rivers, this is not a silent place. On the contrary, the Rhine’s background noise is the relentless drum and bass of the barges – tud, tud, tud – all day and all night.

This is the monotonous sound of successful business. This is the repetitive, trance-like sound of businesses doing the same things again and again, brilliantly, day in day out, without drama. This process is what produces the massive current account surplus, that last week the Americans were complaining bitterly about – which is kind of rich given the Americans have just been caught bugging the phone line of Mrs. Merkel!

But the German current account surplus is a problem in the sense that a current account implies by definition that the country is a massive net lender. This means that German money leaves Germans and cascades into other countries looking for a return. In this way, German banks financed Irish banks and the banks of the other periphery countries. That is what a current account surplus means: the surplus country finances the ones in deficit.

The German current account surplus means that there is a surplus of savings in the heart of Europe. This surplus of savings puts downward pressure on both Eurozone interest rates and retail prices.

The excess savings leave Germany looking for a home and that home might be Irish government bonds, which yield more. But it’s not just Irish bonds, the IOUs of all peripheral governments have benefitted from this German surplus. Long-term rates everywhere have fallen. Could this be more a reflection of the excess of German savings than the notion that the economies of Ireland, Italy, Spain, Portugal or Greece have become better credits overnight? With huge debt burdens in all countries and faltering growth everywhere, a betting man would vouch for the former rather than the latter interpretation.

This week, emboldened by the lower interest rates, our government decided to eschew a precautionary insurance fund and go for the “clean” bailout exit. Let’s see how wise this is.

The government cited the much better financial conditions of recent months, suggesting that we are now in much better times. That may be so, although recent financial history indicates that the worse financial decisions are taken in what appear to be the best of times.

The notion of the best of times is simply an assessment of the ebb and flow of investor sentiment at a particular point in time. The financial markets are always prone to wild swings between greed and fear, between excessive optimism and unbridled pessimism.

Normally the best indicator of where we are is the price. High prices bring high risk, by definition. The higher the price, the more people try to get on the bandwagon, because they believe that high prices are a sign of lower risk but in reality the opposite is the case. As prices fall, risk falls too. Conversely, as prices rise, risk rises too.

In economics, pupils are taught that when the price of something rises, the demand should fall. However, in financial markets the opposite is observed: when prices rise, the herd get on the bandwagon driving prices yet higher, before the whole house of cards collapses and we start again at lower prices.

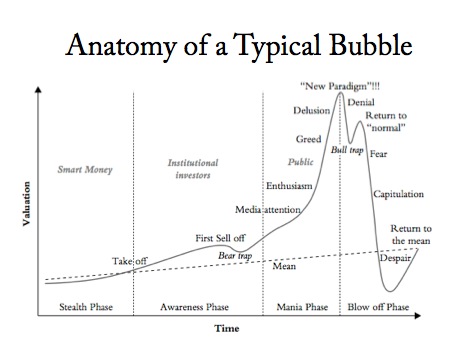

Look at the graph. It explains how bubbles start and how they end and where the value is for the savvy investor. This pattern is observed in all assets from the paintings of Francis Bacon and Andy Warhol, to houses with sea views and to government bonds of countries that are dependent on foreigners buying their IOUs.

The progression is similar in all cycles. Initially the asset is unloved. No one wants to touch it. This is the stealth phase. There are far more sellers than buyers. The assets are going for a song. Then we move into the awareness phase, where prices begin to tick up and institutional investors begin to show interest, committing some capital. Look at the mean price, which is the dotted line and you can see we are beginning to move away from it.

Then we enter the mania phase. This is heralded by media reports swooning over the assets telling us “this time it is different”. Then we get the enthusiasm, the greed phase and we are away.

Irish people know how this story ends. Once asset prices start to fall, not only does the psychology of the investor whiplash but so too does the credit cycle. Credit moves from being abundant to become scarce, cash calls are made and the borrower ends up being squeezed. We’ve all seen this happening.

Now ask yourself what makes you think that Irish government binds are any different to any other asset in terms of this cycle? And where do you think Irish government bonds – an asset whose price has sky-rocketed in recent years on the back of old Germans keeping Euro interest rates close to zero – might be in this age old cycle?

As the barges of the Rhine, laden down with new cars made for export, plough up the great waterway and the productive local Germans take their post lunch stroll on the banks, one wonders if they cop onto what is happening in the Irish bond market again, will that gentle stroll lead to a run?

David McWilliams writes a regular economics column for the renowned German financial magazine “Capital”. They can be seen at http://www.capital.de/

Subscribe to receive my news and articles direct to your inbox

Subscribe.

This great article is written at a time in history that we will read again and compare it with what subsequently happened. What will happen next ? That is ever present on our minds now . How will the Gamble have paid off ? Was there an easier way ? The Markets were never allowed to rescue our Island Economy and instead Politics intervened and allowed to FUDGE the world around us .This has continued since Bail Out days to Exiting Days . Who is really exiting and what ? Who is really being bailed out ? Who will pay… Read more »

David, I know that you like to talk about the ecomomics but Germans have learnt to keep making “things” not bonds. Ireland needs to get back to that, making things. The Germans are closing their Nuclear plants. We should generate nice Green wind power and sell it to them The Chinese are getting a taste for beef. We need to sell it to them. The Chinese dont trust their own Baby formula. We need to sell it to them. The Far East sees Europe as the home of Luxury goods. We must sell Luxuries to them. Them we will be… Read more »

That graph looks very like one that Brian Lucey has published on his own blog today in relation to Bitcoin:

http://brianmlucey.wordpress.com/2013/11/18/bitcoin-bubbles/

So, David, you are now predicting that German savings looking for investment opportunities in the EU periphery countries will flood into Irish government bonds driving up our cost of money just as excess German savings created the late Irish property bubble. Do you really hate the Germans that much or are you so terrified of them drowning Britain economically that you must distort the facts? Every time we forge closer links with Germany you franticly predict our economic demise. You make these predictions in an attempt to deny us the liberating air of modern German thrift and industry and to… Read more »

Pat

You really don’t get it. Why do you think I have devoted many years of my life to learning German, reading German literature and visiting the country? I also write for a German magazine, what part of that don’t you get?

This article is nothing but complmentary to Germany.

David

Are The Germans A Master Race Or Are We So Dumb ? Anyone Would Think The German Surplus Was Donated To The Poor To Pay Water Tax Could Not Be Further From The Truth Germany Gets A Handsome Return For Its Perceived Kindness . And What With Donkeys Paying 40% Of All EU Debt They Should Have Twice As Many Barges Next Year? Germany Learned A Lot Since The Bismarck When A Good For Nothing English Plane Blew The Steering wheel Off It , Sights On Bismarck Set To High All The Rag Tag Plane Had To Do Was Go… Read more »

Great article. The very true but depressing phrase “recent financial history indicates that the worse financial decisions are taken in what appear to be the best of times” points to humans and their herd mentality. The Insiders know it, the Politicians know it, the media feed it and a lot of us get hammered as a result. German money may be sloshing around for a good deal and certainly our higher bond returns will be leveraged. It means Ireland has to produce substance in a very open and MORE unpredictable environment. Balancing input costs to businesses versus sustainable public services… Read more »

5Fingers: “Great article” does this mean that you buy into David’s assertion that a German current account surplus is bad for the Euro Zone as a whole because German savings must AUTOMATICALLY flow into the peripheral deficit countries driving up bond prices and making them ever more dependent upon Germany?

David saying here that a German current account surplus “is a problem” is like saying that a son who is frugal and has his shit together is “a problem” for his siblings who are wasters. If David thinks so highly of Germany he should be saying that we need to be imitating them not blaming them for our “problems”. You are right 5Fingers “we need to export and strengthen trade with Germany” – and with the rest of the world. We need to strive for a current account surplus by exporting – like Germany. The Euro Zone is fortunate to… Read more »

I was in Köln last week too, will be working from there quite a bit over the next few years. Lookkit…even Sunday magazine supplements have been advising to invest in periphery bonds. Articles like this praise investors who have done so. :http://www.finanzen.net/nachricht/anleihen/EURO-PERIPHERIE-Randstaaten-ueber-den-Berg-2576961 German money is creating a massive property bubble ‘Betongold’ with Banks loosening lending practices and estate agents up to their old tricks of sales’ puff. Strangely it doesn’t appear in this column but here’s a taste from wsj blog: http://blogs.wsj.com/economics/2013/10/21/germanys-central-bank-warns-of-local-housing-bubbles/ It would be nice to call this one as well as the Irish bubble that went before :)… Read more »

Pictures are better though : these are clear as anything…..

So you think lack of German demand is not a problem?

Two charts…

German consumption Expenditure and German Household and Government Consumption Expenditure v rest

http://brianmlucey.wordpress.com/2013/11/18/so-you-think-lack-of-german-demand-is-not-a-problem/

Germany has had major productivity over 4 different currencies, Reichsmark, Rentenmark, DM, and now the toxic Euro. Why? Very simple – Bismarck. When he was fired, he warned about a “7-year war” planned and executed. That old geopolitical humbug of the Brutish is today, rather a rattle.

The UK is getting along quite nicely and building Hinkley Point nuclear reactors, while Angela is doing the Brutish bidding with “renewables”. I’m afraid DMcW it either totally awash on some “red wine”, or simply posturing, posing, a Tiger preening.

Dorothy, if too low ECB interest rates start to lure German investors into risky peripheral bond yields the Bundesbank will simply rein in the free money being pumped into the Euro Zone economy by the ECB.

Unlike the U.S. where the Fed is controlled by Wall Street not the U.S. Government the ECB is effectively controlled by the German Government. That is what drives people like David McWilliams crazy.

What is driving people crazy is the savage austerity imposed all over the EU ans USA in the name of monetarism. The AfD (Alternativ für Deutschland) campaigned in the recent election on nothing other than National Monetarism, a modern variant. What is even crazier is Germany is the worlds leading example of reconstruction, and the memory is still vivid. So instead of national monetarism of various brands, including Irish, A Marshall Plan for Greece and the Med. A part of the Eurasian Landbridge, postponed by the Balkan wars, and now by Syria/Libya. We have huge reconstruction to do and Germany… Read more »

What is being done to the transatlantic region is WORSE THAN “WEIMAR”!

Weimar you may ask? 1923, Germany, hyperinflation. The Torygraph, DT, et al (DMcW) seem to lust for a repeat of Weimar 1923. How this is supposed to fix anything only someone with “pieces of eight” for a brain could fathom.

The current generation has been exhorted time after time to consume. We are a consumer society we are told over and over again. No mention of production first. So we went out and consumed more than any previous generation. We consumed our past , present and future. We borrowed cash on credit to do so. Germany has a collective memory of having been so consumed in the past that they know you cannot eat what you do not grow. You can not consume what is not produced. Production before consumption should be our new battle cry. Investment made from savings… Read more »

Germany has problem number 1 worldwide right on the doorstep. See the (zerohedge) 2012 financial report page 87 : At $72.8 Trillion, Presenting The Bank With The Biggest Derivative Exposure In The World (Hint: Not JPMorgan) Have a look at : German GDP v. Total Derivative Exposure. Euro 2.7 Trillion v. Euro 55.6 Trillion. But don’t worry, this €56 trillion in exposure, should everything go really, really bad is backed by the more than equitable €575.2 billion in deposits, or just 100 times less. Of course, a slightly more aggressive than normal bail-in may be required in case DB itself… Read more »

‘Anatomy of a Typical Bubble’ concludes with ‘will that gentle stroll lead to a run’ ?

Can we call that graph a Penis and what comes from that is diarrhoea . What else ?

Germany is a business

and the rest of Europe are bad customers..take up too much time & energy for low return.

Germany will or is developing stronger business relationships with Russia & the Far east [China]. When she feels secure enough she will cast aside the weak & co-dependant Countries of Europe & bring the strongest with her in a new economic pact with Russia & further afield.

Probably being done as we speak.

Russian Balls

German Ingenuity

Amerika will be pissed

Barry

Far from the Germans coming into Ireland and enslaving us with torrents of cheap loans, as McWilliams and other pro-British writers have convinced the gullible Irish public, it was the Irish Government that lured the German bank Depfa into its unregulated banking/tax haven called the IFSC. In fact, in order to attract Depfa into the IFSC, the Irish Government enacted company-specific legislation enabling Depfa to operate from Dublin with zero regulation in the United States. That was hardly a friendly act by Ireland towards either Germany or the United States. The German people ended up taking 100% ownership and bailing… Read more »

Germany’s success? Income poverty / Low wages: One in four! Needless to comment any further that McW now writes for Gruhner/Jahr junk content provider Capital. They take anyone who can construct a half decent sentence and supplies them with the idedoloically manufactured mainstream poison. The bottom line is that low wages and resulting income poverty are some of the real “success” driving elements. Superfluous to explain that the low interest ECB policy continues to destroy the rest of the midle class wealth while the tax- and bailout burden induced by banksters and their political cronies is doing the rest. There… Read more »

I must admonish the above contributors to this great article .What should be following from this is about what happens next .This article leave a question mark at the end and this is not been addressed by the contributors .Why don’t we focus on this matter only .

And to think that no one even mentioned the absence of the ‘ precautionary credit’ that our Minister for DOOM had failed to achieve.

I think if your contributions were assessed as part of an Exam most of you would fail.

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/11/18/opinion/krugman-a-permanent-slump.html?partner=rssnyt&emc=rss

A Permanent Slump? (USA)

Krugman obviously reads this thread as I’ve been saying this here for years and the rascal has gone and plagiarised me. David, you need to have a ‘word’ with him.

“The view from Germany” Can ya see your house from Germany. We have ghoulish estates here that we soon will not see, yet one is given the impression that no one needs them while at the same time our government pays out money to the homeless to help keep the banking Zombies house well fed. Knocking down houses while people are homeless has brought us back to the famine era, whom do we blame this time! What will the history data storage record – what accompanying soundtrack will be chosen and who will reprise the role of Trevelyan. Welcome to… Read more »

Michael, I agree with you that short sharp recessions (which used to be called the business cycle) are necessary. Bull and Bear markets for example require such corrections to enable profits and losses to be realized. You can’t have an endless summer of profits with no losses. Unfortunately Larry Summers and the Harvard Business School taught countless MBAs that you could. This endless “Summers” fantasy is now threatening to destroy the world economy. So what is to be done? How do we let the air out of the resultant massive asset bubble without bursting the whole balloon? How do we… Read more »

Someone brought up Krugman.

Larry Summers: Depression will Continue, until you Die

— As reported by fellow economist Paul Krugman in his Nov. 17 column “A Permanent Slump?,” Summers emphasized that the “depression-like” (Krugman’s word) conditions enveloping the U.S. economy are the “new normal,” and that no one, including him, has a clue of how to create a real recovery.

The only thing to do? Keep up the Quantitative Easing.—

Utter moral bankruptcy from Krugman and Summers.

Odd that that escaped the commentators here.

Larry Summer’s endgame memo… meeting with 5 banking CEO’s to mould US financial policy. Greg Palast, love the Mickey Spillane type fedora. Let’s all jump off the banking deregulation cliff…. Wheeeeeeeeeee. . . http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=96Z2puRTIls He refers to Larry rather affectionately as the “Typhoid Mary” of Economics. One of the people that confirmed the content of the memo was Joe Stiglitz. who was in Clinton’s cabinet. He said that Summers would sit in cabinet meetings and when they would talk economic policy he would turn to Ruben and say “What would Goldman think of that, what would Goldman think of this..?”… Read more »

Greece.

“The rise in violence and hate-crimes is no surprise. The official unemployment rate in Greece is 28%, and over 60% among young men. No wonder desperate youths are wrapping batons in Greek flags and beating immigrants: When people are pressed to the wall, they hunt for their tormentors –– and too often find their fellow victims to blame.”

Economic devastation breeds fascism. No s**t Sherlock! :O

http://www.gregpalast.com/the-golden-dawn-murder-case-larry-summers-and-the-new-fascism/#more-8710

Been on this site for almost five years and have been saying this from the early days – didn’t need Russell Brand and Morrissey to tell me but more people will listen to them:

http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/music/news/morrissey-backs-russell-brands-no-vote-call-in-tirade-against-british-establishment-8949902.html

Voting is a charade and a total waste of time. The best way to vote is not to vote at all.

The contagion decimates USA and now heading,with intensity, to PRC

“But it’s fairly obvious that this step would lay the groundwork for full privatization of the banking system down the road.”

http://www.slate.com/blogs/moneybox/2013/11/15/privately_owned_banks_in_china_coming_soon_in_another_major_reform.html

We surely don’t need John of Patmos or The Oracle to tell us “The 6 trumpets” are the wake up call, right?

short

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3T-VAi2Xqq8

Just a thought…if this economics blog was in Germany…and the contributors were German…..would the comments be so loosely grasped in common sense, logic, rational analysis, or even relevant reality ? Some of you simply watch too much RTE, to have developed any useful intellectual models for parsing the reality where we find ourselves. Yes, the Anglo economic model is based on Ponzi-economics. The three losers of WW2 are banned from joining in the power sharing arrangement of the Ponizi racket. So they became producers, instead of imperialists. Same applies to the loser in he Cold War. Except Russia (plus Ukraine)… Read more »

David is right to give the “bubble” example. Massive problem with the current “recovery” which never involved any defaulting – unless you were Cyprus, it is not cleaning the system of it’s stupidity. Capitalism is supposed to be a competitive system. Currently, the banks are competing for lobbying access in Brussels. They are no longer looking inside their own systems. Perhaps this has something to do with organization politics. Perhaps it might even be derived from labour law. And of course, a lot of it is the idea that creating internal disenchantment will result in some media organizations getting the… Read more »

That’s an interesting read Adam,thanks.I wished they would just stick with GS and not amble down the by-roads of all other ,impotent,regulatory measures,especially now when time is running out! From “TheDog&Frisbee” “Modern finance is complex, perhaps too complex. Regulation of modern finance is complex, almost certainly too complex. That configuration spells trouble. As you do not fight fire with fire, you do not fight complexity with complexity. Because complexity generates uncertainty, NOT risk, it requires a regulatory response grounded in simplicity, not complexity” So keep it simple,stupid is the recipe to bake this particular cake.Glass Steagall is exactly that –… Read more »

Pretty! This has been a really wonderful post. Many thanks for providing these details.

This is my first time pay a quick visit at here and i am really happy to read everthing at one place