Last week, there was lots of talk about individual politicians but, in truth, these people – although mostly well-intentioned – don’t actually matter in terms of the economy. All the main Irish parties believe in the same economic orthodoxy, so in a sense they are irrelevant. Remember, it was economic orthodoxy that got us into this mess, so it’s hardly the most likely route out of the crisis.

A politician’s fate is controlled by the economy, rather than the other way around. If they chose an economic vision and were prepared to do something about it, then things would be different, but they don’t have such a vision.

Amazingly, Irish politicians and the civil service have manoeuvred themselves into a position where the acid test for success or failure is whether the budget deficit goes up or down.

However, the budget deficit is an accounting residual – it has very little to do with economics. It is a figure that falls out of national accounting models. It is the end point, not the starting point.

As such, it tells you very little about what is going on. This figure’s irrelevance is made all the more compromising by the fact that the other target that political spin-doctors crow about is the bond yield. But the bond yield is only a momentary value judgment made by the same infallible financial markets that lent billions to Anglo, didn’t see the crisis coming and can’t price risk.

So what’s going on? Why do people vote for Sinn Féin if there is a recovery, and if there is a recovery, do you feel it? Or is this yet another chimera, driven by yet another entirely manufactured housing boom?

What I have decided to do this week is bring you four up-to-date separate charts, which tell us not so much what is going on in the Irish economy, but why it is happening.

In addition, these charts may explain why people voted the way they did last weekend.

Chart 1 tells us what is going on in the real economy. It reveals that, while inflation is falling, wages are falling even faster than prices, and this means that people’s purchasing power is actually falling, not rising.

The key figure to look at here is the real wage – the red bars on the graph. This is your wages minus the rate of inflation. The numbers show that, even though unemployment has fallen in the past two years, so too have real wages.

This is why you feel poorer, not richer, despite the fact that everyone says there is a recovery in place. For the economy to feel prosperous, real wages have to be positive – they are now negative, and have been since 2011.

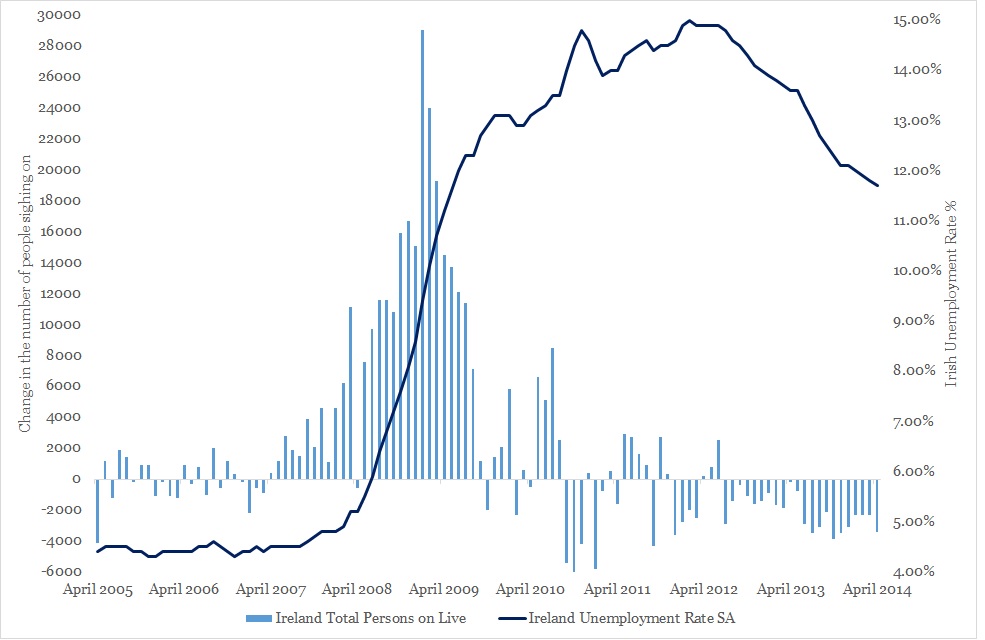

Without real wage growth, there can be very little prospect of sustained demand. Without sustained demand, there won’t be a sustained fall in unemployment. We can see this development in Chart 2, which not only shows us the rate of unemployment but the amount of people drawing the dole.

What we know from the latest figures, published last week by the CSO, is that employment growth has stalled.

In the period from January to April, the number of people in work rose by just 1,700 or 0.1 per cent quarter-on-quarter, compared with a 10,600 gain in the fourth quarter of last year.

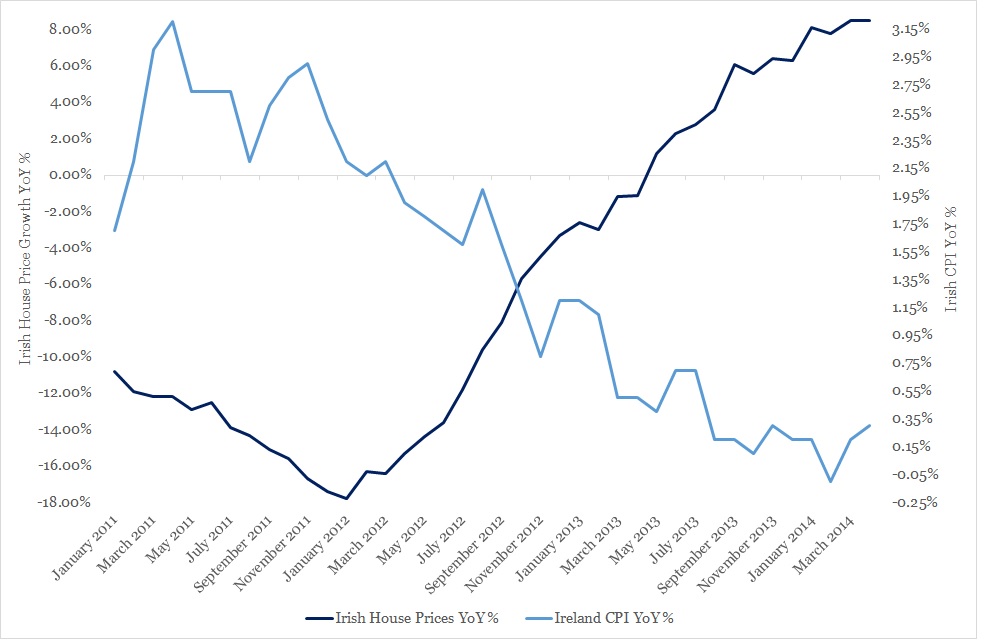

The lack of jobs and demand means that the rate of inflation has continued to fall. You can see this in Chart 3, which shows you the rate of change in general prices on the one hand, and house prices on the other.

This is very worrying, because it shows us that prices in general are heading downwards, but house prices are heading skyward.

Why is this a problem? It’s a problem because your wages are linked to general prices, so as wages keep moving downwards, house prices move upwards. We know from Chart 1 that real wages are falling, but house prices are soaring.

This means houses are getting more and more expensive, but the only way the average person can afford a house is to borrow and borrow as much as possible, because wages and incomes are not keeping up with house prices. We’ve been here before. Don’t you remember the madness?

You may now be starting to get the picture.

Let’s look at the final chart.

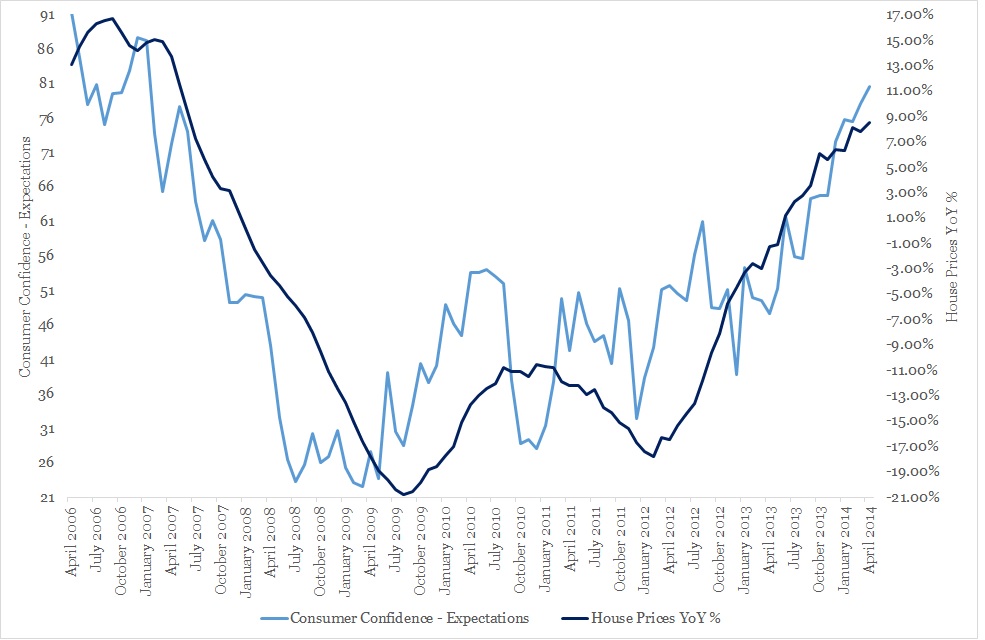

Chart 4 shows the impact of house prices on consumer sentiment. We can see that as house prices started to rise, so too did consumer confidence and this shows the phenomenal impact that housing wealth has on how people feel about the future. You can see that as house prices fell, consumer confidence fell in tandem. At some stage, one drove the other. Then in 2012, house prices started to move forward gently, so too did consumer confidence.

In the past few months as the property frenzy has taken hold again, consumer confidence has skyrocketed too.

But what else is driving this confidence?

Job growth is slowing down, so it’s not jobs. Real wages are actually negative and inflation – the price at which Irish small business can sell its products – is falling.

What is driving Irish confidence is the housing market. So here we go again. Seven years after a housing boom almost destroyed the country, we are at it again and there are enough people who benefit from the positive wealth effect of a mini-housing boom to keep the whole thing going.

This is not a sustainable economic model. We are heading back to the place where we Irish people buy and sell Ireland to one another with other people’s money and call it a recovery.

As prices rise in certain areas, the people who live and already own houses in these areas feel richer. They feel able to spend. Maybe they draw down savings that they squirrelled away and consumer confidence takes off.

But they are the already rich in the main. Also crucially, the rise in house prices does help those in negative equity, but unfortunately where house prices are rising are not the areas which are suffering from negative equity.

As houses prices rise in selected areas, and large parts of south Dublin become to Ireland what Knightsbridge and Chelsea are to Britain, the rest get left behind and feel that they are not included in this so-called boom.

The media hypes the thing up, because the papers and radio stations make money out of the property advertising, and this further reinforces the “us and them” division.

Is it surprising, in this context, why people reject mainstream politics?

If wages were rising and houses were affordable, there would be an entirely different political narrative playing out. But this is not the case.

As long as mainstream politicians and parties are happy to preside over such a lopsided economy, which in turn results in a divided society, radical politics will become mainstream . . . and mainstream politics will become redundant.

Subscribe to receive my news and articles direct to your inbox

It took so long to log onto your site I have forgotten what it was I was going to say.

People in glass houses etc. etc.

Fix your site first then advise how to fix the country.

Sinn Fein it is so !

Subscribe.

Having a good job in Dublin no longer cuts it. Can we blame the politicians – absolutely.

I think graph #4 is accidentally a copy of graph #3. Great article though, as someone running a small biz in our still bamboozled economy, price deflation is still a big problem for us, and sadly it is hard to see a proper recovery ever emerging, where wage growth is happening and people are not still absolutely shítting themselves in relation to their spending. We certainly do lack a vision in this country. The idea that we might have an economy where private housing is affordable, at the highest political level, there seems to be this notion, “who do you… Read more »

Anyone have any info on the grant scheme for house extensions in the last budget? Never heard another thing about it. I figured it would only drive up the value of the house and Revenue could then look for more property tax. Why let them know about any extensions if that is the case? As for the boom in Dublin, they get what they deserve, I was under the impression that prices had actually landed at about 10% above what they should be and were still too high. Looks like they want to pay more property tax up there. Good… Read more »

David, Spot on again with the analysis , but I would disagree with one statistic – the CPI negative growth in 2014. I have been tracking a general basket of food in both Tesco & Dunnes over the last 2 years and have seen the same audacious price rises each year in the Jan/Mar period. I’m not talking 1% – 2% but wholesale jumps in basic foods of 15% – 33%. This is not done with just price increases but also in tandem with ever shrinking product unit size. If you doubt this take a close look at the individual… Read more »

It explains why my usual yogurt carton is not full any more and my crisps are only in the bottom of the bag .

It seems if they can seal it …they can bag it too .

Its time to insist that the Mega Supermarkets publish all Irish Sales Revenue and Profitability

They work on roughly a 38% margain as far as I can tell. Figure it out.

[…] the only economic measurement that seems to matter to elected Irish politicians – is “an accounting residual“. It is not the economy, it is the cups in the sink, the bottles on the counter and the bin […]

Hi, There are two aspects to this article that need to be considered to create context. They are; Author and content. First of all the narrative coming from the author indicates a maturity in understanding of how the real politick of a society blends into economic realities which is refreshing as some of the articles of yesteryear were hopelessly naive in this regard. There is also the fact that your conclusion ends definitively on this occasion with a clear statement as to how you think your analysis will affect the economy and politics of the situation. This is also refreshing… Read more »

[…] full article at source:[embed]http://www.davidmcwilliams.ie/2014/06/03/property-here-we-go-again[/embed] […]

The true value of an asset is what people are willing to pay for it. Unfortuantely Irish consumers are being all too easily manipulated again. I have lived abroad for 10 years and watching the income disparity, continued corruption, forced emmigration, and economic delusion is both frustrating and sad. Without competence & accountability in government Ireland is doomed to repeat the mistakes of the past. Sweeping statements: Ireland has a housing shortage yet it’s full of ghost estates. Ireland has record levels of homeless despite NAMA asset ghost estates. Ireland rewards you to turn down work in favor of social… Read more »

In the first paragraph you describe politicians who have been in the media recently as been ‘mostly well intentioned’

I totally disagree.

I think that most of the politicians in both the current government and main ‘opposition’ are Anti Worker and serve only themselves and their corporate and banking masters who have developed a corrupt system to legalize bribes in such away that they are not breaking any legal law, instead they pay them grossly over fattened wages and pensions.

These politicians and the corporate media which defend them disgust me as do most journalists.

I should add that the remainder of the article is both informing and accurate.

On TV3 one evening, they were asling Ming about his canvassing. He outlined how he had met people across 15 counties who were in business and who were struggling. And he suggested that this was a better measure of the economy than any of the nonsense from the ESRI. He stated that the ESRI should go and meet the people and they might learn something about the economy. Ming is 100% correct. What Ming is saying is reflected in the article above, and also in the blog commentary from Constantin Gurdgiev. The statistics that are being measured have less and… Read more »

Until we tackle the issue of housing density in Suburban Dublin, and the manner in which it drives up property prices, this saga will just get repeated, again and again.

And still NOBODY is prepared to talk about the issue in public.

I am glad to hear that the ESRI is now taken with a grain of salt. It is about time we realize that the ESRI doesn’t have sufficient data to make a good story. Daft.ie is another joke that we should be aware of.

So this morning I read this.

http://www.irishtimes.com/business/sectors/technology/value-of-ireland-s-digital-economy-set-to-soar-1.1820769

Which appears to be entirely underpinned by the following statement:

The growth of the sector will be fuelled by a rise in consumer spending, which accounts for about 60 per cent of the overall 2020 value estimate.

Which one is left to assume will, in turn, be fuelled by the froth of a property boom. Encouraging businesses to conduct more transactions online doesn’t necessarily increase people willingness to increase their spending. Your right David, the propaganda war has started it seems.

Ah the Government. It can fix everything. If only there was a regulation. the trouble is the government is not doing its job. Why if only we had the right government everything would be fine. this government is too small we need a bigger one. When o when are the dependent minds going to free themselves of government control? Has it not crossed your feeble brains that governments are the causes of the problem and not the solution. On course not. Here is a country ruled by a foreign government for 800 years that could not wait to throw it… Read more »

At the present rate of growth Dublin’s property will be back to boom time levels in 2 years, and twice as expensive in 5, then four times as expensive in 8. Thats the nature of super exponential growth. And 25%-30% is exponential. The “soft landing” people are hoping that mortgage lending will increase, as supply increases ( as of course it will if there is a buck to be made, and the construction sector is responding even now). However retail mortgage rates are high by the standards of the boom – already the average 340K house in Dublin can only… Read more »