Forty years ago this weekend, at the Geneva peace conference between the Arabs and the Israelis, the Israeli foreign minister and one-time Belfast resident, Abba Eban, declared of the Palestinian negotiators that “they never miss an opportunity to miss an opportunity”.

Eban – born Aubrey Eban – was a great believer in trading land for peace and when seen now with the benefit of hindsight, it’s clear that the Israeli leaders of the 1970s, like Eban, were just the type of people the Palestinians should have dealt with – but didn’t. By holding out for a better negotiating hand, the Palestinian leadership could accurately have been characterised as never missing an opportunity to miss an opportunity. Now Israel is a different country; its shift to the right is permanent and today, the Palestinians have fewer influential friends than ever.

When looking at how our government is handling Ireland’s mortgage timebomb – the one obvious internal landmine that could blow the country’s economic recovery apart – you might quote Eban’s quip about missing opportunities.

The mortgage problem hasn’t gone away. We are still the most indebted people in the world.

The time bomb has been temporarily defused by incredibly low interest rates helping to push up house prices and push down negative equity. A boom in our real trading partners, the US and Britain, has allowed many Irish companies to weather the domestic slump of the past five years. It is no surprise that when the English-speaking world moved out of recession in 2011, it dragged its reticent cousin, Ireland, up too.

We have benefited too by the fact that our so-called partners in the eurozone are in trouble, driving down rates to the lowest level since the 16th century.

Incomes are slowly improving and there is effervescence in the economy, partly due to the pent-up demand of money that hasn’t been spent for six or seven years.

However, it’s clear for anyone who takes a long-term, mortgage-length view of the world that interest rates will rise at some stage and, when this happens, it is quite likely that we will experience another mortgage default crisis. The reason is simple: many hundreds of thousands of people – mainly those on trackers – can just afford their mortgages because interest rates have never been lower.

Just to get an idea of how precarious the situation still is, look at the latest figures published by the Central Bank.

Despite the fact that interest rates in Ireland are at the lowest for 500 years, the number of accounts in arrears over 90 days in Q3 was more than 117,000. There has been a small improvement in this figure in recent months.

If the situation is still fragile, why is there not a greater incentive to consider what might happen if the rate environment were to change?

The relatively sanguine approach to the mortgage time bomb can be explained primarily by the fact that property prices are going up and going up quickly. This is repairing the balance sheet of the Irish banks at a much quicker rate than many imagined possible even a year ago. So there is no incentive for the banks to try to do anything about the overhang of mortgages that could turn sour in the years ahead.

The banks have been focusing on having enough capital. Bank capital is only all the assets of the bank added up and all the liabilities subtracted. So if assets are rising, then the bank’s capital looks better, so there is no need to worry. When property prices were falling, the banks’ capital was being wiped out and so, in order to prevent bankruptcy, there was huge incentive to get these bad loans off the banks’ balance sheets. No there is no such incentive.

The easiest way to deal with a bad loan now is simply to roll it over. As my old mate the former US bank regulator Bill Black explains, when speaking about the banks’ current attitude, “a rolling loan gathers no loss”.

After years of trauma, the Irish banks are happy as long as there are no losses today, so they might worry about tomorrow but don’t care about one year hence – and as for five years ahead, well that’s an eternity.

While the banks’ management might be able to behave like that, the managers of the country can’t. The state shouldn’t be so chilled about the possible impact of higher rates in Ireland. Because we have such huge mortgages, Irish incomes are very sensitive to changes in interest rates. When rates fall, our incomes recover, but when they rise the impact on Irish after-tax incomes is amplified by the size of our borrowings.

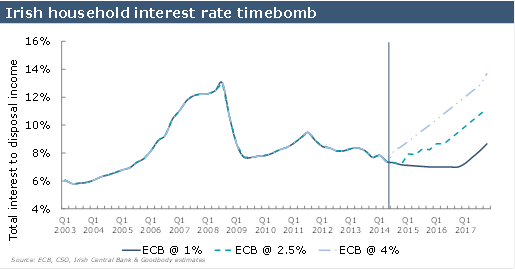

Dermot O’Leary, chief economist at Goodbody Stockbrokers, has examined the impact of a return to “normal” interest rates in Europe and has come up with this wonderful chart.

Looking back to 2004, you can see modest rises in interest rates; the huge increases in debts caused interest payments as a percentage of disposable income to rise rapidly from 6 per cent to 14 per cent. As interest rates collapsed after the crash, so too did interest repayments as a proportion of income.

Now look at what would happen if rates were to go from where they are now (0.7 per cent) to 2.5 per cent and then to 4 per cent (which is a historic norm). You can see that, very quickly, interest payments as a proportion of income would move up rapidly.

This would cause Irish disposable income to contract very quickly, and consumer effervescence to disappear overnight, leaving another mountain of debt.

So what could be done to avoid this? Is there an opportunity to take this debt (these tracker mortgages) off the banks’ balance sheets? And if so, would we be mad to miss an opportunity?

At the moment, the ECB under Mario Draghi is doing its best to get European banks to wrap up all these types of loans into what’s called “asset-backed security” instruments and loan them to the ECB in return for cash.

The ECB is bending over backwards to get these loans off the banks’ balance sheets in order to encourage the banks to use the cash to lend out to get the Eurozone economy going again. This is a huge opportunity for us.

If we can get the trackers off the banks’ balance sheets, we pass the risk on to the ECB. Who knows, given its proclivity for the unorthodox, the ECB may be persuaded to take equity in the banks in a debt for equity swap. Why not? The ECB has broken all the rules in Draghi’s quest to turn the euro into the lira, behind the backs of the Germans, to save the EU economy.

This is the opportunity, and it is staring us in the face. As long as the European economy is a basket case, which it is now, the ECB will try all sorts of stuff that it won’t when things recover.

However, Draghi won’t be around indefinitely. Last week there were signs of a mutiny at the ECB with the Germans saying enough of all this Italian flexibility. The opportunity is to negotiate with the practical Italian now rather than the hardline German who will replace him in in the years ahead.

Will we take this chance, or will we revert to form and never miss an opportunity to miss an opportunity? That’s the question.

Subscribe.

I’ve just started reading Thomas Piketty’s book ‘Capital in the Twenty First Century’ David and he reckons that interest rates might stay at their current level for another generation, or even 40 years.

Therefore indebted people might leave it to their kids to worry about, even if that’s not their direct intention.

Have you read that book and what do you think of that prediction?

And to answer your final question, of course we will miss the opportunity – we always do.

Couldn’t agree more with you, Adam! The shower of gobsh*tes that are supposedly governing the country will do their best to miss this opportunity and then we’ll more than likely end up in even deeper doo-doo!

My preferred fix is simple. 1) Seize the houses of those in arrears over the next year pushing them onto the rental market, meanwhile building supply. 2) Change the rental laws to be like Germany etc. This will allow those who were prudent during the boom, or not old enough to be imprudent to get onto the ladder at the expense of a fair amount of people clearly taking the piss because the State owned banks won’t touch them. It will remove future bad loans from the books, and make housing cheap for new buyers so we also have the… Read more »

My Variable loan with AIB has only gone UP in the last few years – as ECB rates dropped, AIB et al have been raising Variable Rates to compensate for losses on Trackers. So, I like hundreds of thousands of mortgage holders on Variable rates have not seen our percentage income to repayments drop. If ECB rates drop, we get hit. If ECB rates rise, we get hit. We have not enjoyed the same benefits as tracker &/or fixed rate from the government on this matter, despite them holding a 98+% share in AIB. If the government forced AIB and… Read more »

Can someone explain what a tracker mortgage is? I was thinking it was a variable rate loan, but after reading CorkRob’s comment I’m thinking maybe not.

Also, I’m dying to know why every comment section starts with Mr. Byrne weighing in with “Subscribe.” Do you have to subscribe every time, Mr. Byrne?

It’s minus 13 C. here in New England. Our dirt road is a sheet of glare ice. And they wonder why I’m moving to Ireland…

Good idea, as long as the kids are not legally liable for the mortgage if they don’t want it – they should be free to walk away with whatever their parents have put into it (adjusted for A, B and C -eg. inflation, depreciation etc.) and then the bank or whoever, can have the rest of the value.

What would happen to me if my tracker goes the way David wants it to go ? I have no problem paying at 1.75 % right now and never had a problem paying my mortgage . In fact as the interest rate is so low we can save money at present . I don’t want to lose my tracker . Is that what David is saying should happen?? If so then I’ll lose out considerably along with many others .

It’s good journalism from David that his figure of 117,000 mortgages in arrears for more than 90 days, includes the figures for BTL mortgages as the Central Bank keep the statistics for owner occupier and BTL mortgages separate – an issue which seems to mislead certain business columnists (who will remain nameless!) and hence inadvertently mislead the public. The total value of all mortgages is around €135 billion. http://www.centralbank.ie/polstats/stats/mortgagearrears/Pages/releases.aspx What surprised me at first is that the average value of a BTL mortgage is around €201,000 (according to these Q3 Central Bank figures) and the average owner occupier mortgage (or… Read more »

That’s an incredibly stupid idea. Really. You are assuming that this vast increase in credit would allow people to buy the average house at 555 euro ( I am sure that is an over-estimate of the per monthly cost but lets go with it). In fact given the competition for houses house prices will shoot up. All house purchases are won by paying more than the other guy, so with housing supply contained prices will go up to the level that the buyers who can pay the existing monthly payments are comfortable with now. So if the average house now… Read more »

“If we can get the trackers off the banks’ balance sheets, we pass the risk on to the ECB.” Are you saying that the ECB will not require a re-purchase (buy-back) agreement, as did all mortgage-backed security instruments created and sold by the Irish banks during the boom? Is that what you think Draghi is proposing? Is that the opportunity you think is knocking? If the ECB, or anybody else, was to buy mortgage-backed securities without a repurchase agreement it would undermine the entire asset-backed securities market. Therefore your premise is misplaced. There is no opportunity to “get trackers off… Read more »

Interest rates staying low for years will not solve the national problem:

Firstly, cheap money makes speculative investment more attractive over productive investment.

Secondly we’ll have an increasingly expensive problem of pension poverty, which absorb a greater and greater proportion of GDP.

I’m surprised at David trying to punt the idea of a free lunch.

“The ECB has broken all the rules in Draghi’s quest to turn the euro into the lira, behind the backs of the Germans, to save the EU economy”

Saving the EU economy by turning the euro into the Lira?

Do you remember there was a prolonged bank strike in the 80’s I think. Did the economy collapse? No. people simply wrote IOU’s and life went on.

The economy won’t be saved by dicking around with currencies.

The idea of problems and solutions around the length of mortgages cropped up during the Great Depression. At that time, mortgages were typically 2-5 years long. They worked on the idea of a down payment, then interest payments for the duration and then a balloon payment. If a person could not meet the balloon payment, they could refinance. However, this all stopped with the Depression. The market came to a standstill. So the Federal Housing Association said they would provide insurance to lenders. If a house was in negative equity and the house was dumped, the FHA would meet the… Read more »

Forecast 2015

The economic outlook for European banks in 2015 will be hampered by weak profits, risks of bail-ins and litigation charges, Moody’s Investors Service announced Monday.

Sterling Base Readers – Take Note Higher rates are coming – take action now Whatever happens, the Bank’s report – and the confident tone – makes it pretty clear that the plan is for rates to go up at some point in 2015. The autumn looks most likely at the moment, according to City forecasts. But the Bank might even be laying the groundwork now for a rise in the summer. This means that if you own a home, or are buying one, it makes a lot of sense to lock in low interest rates now, by getting a fixed-rate… Read more »

An opportunity to fcuk up was recently taken by Heineken. Wetherspoons are determined to offer their customers value. By doing this, they are exposing the gombeens for what they are. So the captains of gombeenism have embarked on more gombeenism to avoid making the pub market a fair place to do business. But the giant Wetherspoons are taking no sh1t now, and have raised the stakes. All of this could have been avoided if the gombeens had stopped being gombeens. But in a week where RTE are happy to offer Ray D’arcy €500,000 a year to talk to the nation,… Read more »

Hi Colin, It certainly has. I don’t drink any of the products mentioned but if Wetherspoons can knock out Heineken for 3 Euro and make a profit and most pubs are charging in excess of 5 Euro that is serious profit margin. Even factoring in Wetherspoons buying power something is seriously amiss. The bizarre thing is that people get worked up over alcohol prices. Regional UK presenters serving a similar market and demographic would command £130,000 at most. What justifies the other 335,000 Euro for Mr. D’arcy’s services paid for by taxpayers? When buying a house in the UK the… Read more »

All markets are corruted by the money masters. This corruption seeps into the general business models as eventually markets are destroyed. Only the manipulation remaims. Money and wealths is syphoned off to the elite and the rest of us are deprived of our just rewards. No matter what is debated above it is inconsequential until the basic problem is solved. “It matters because the rigging of the gold market is the rigging that facilitates the rigging of all markets — part of a much broader scheme by which a secretive and unelected elite in the United States and Western Europe… Read more »

I wonder where David gets his information about what is going on within the ECB and why he thinks the Germans will regain (?) control of it.

While the Germans seem to have clear (perhaps simple) ideas of right and wrong and like following rules this doesn’t necessarily mean they are any more rational than others.

A lot of things can happen before interest rates are (or not) increased.

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More Informations here: davidmcwilliams.ie/opportunity-knocks-but-will-we-take-it/ […]