When I was a boy I never went to a restaurant with my parents. On very special occasions we might go to a hotel grill room. Restaurants were for other people, of a different caste. Restaurants signified not just wealth or commercial status; a more adventurous palate indicated a subtle form of worldly sophistication.

Back then, appreciating the aromatic delights of ginger facilitated your entry to rarefied strata. Not anymore. But while restaurants may have lost some of their social cachet, they still reveal, sociologically, something about a place.

So, let me introduce a new indicator of economic development, the TripAdvisor index of economic vibrancy. This measures the number of restaurants reviewed on TripAdvisor in any town. Restaurants capture economic dynamism, disposable income, demography, and social vibrancy, all of which, when added to hard numbers, help give a sense of a place.

Simon Coveney’s recent remark that he would like to see a united Ireland in his lifetime prompted me to compare the TripAdvisor indices for the Republic and Northern Ireland. If we are talking about a united Ireland, we should know what we are dealing with.

So, before we talk restaurants, let’s talk people.

Ironically, despite the fact that Ireland’s future is framed in demographics, demographics are rarely actually examined. Without data, we just have opinions; with data, we have forecasts.

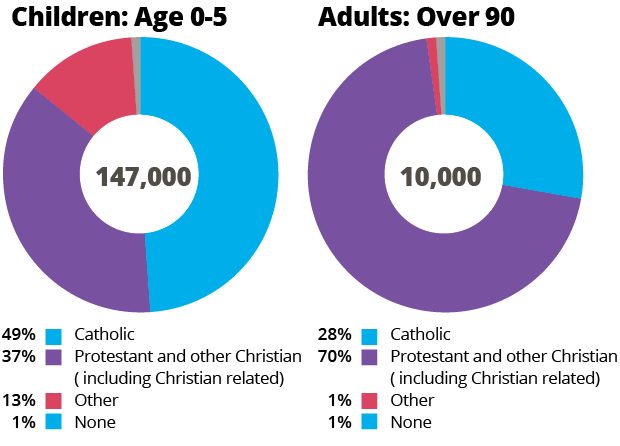

Data from the 2011 census in of Northern Ireland show the Protestant population in the North is falling more quickly than most appreciate. The Catholic population is doing the opposite. One striking number is the comparison, by religion, of the very oldest cohort in Northern Ireland with the very youngest.

The Catholic population of children, as a percentage of the total, has nearly doubled in 90 years while the Protestant population has practically halved.

In the over-90s the religious split is 70 per cent Protestant and 28 per cent Catholic. There are just over 10,000 people over 90 in the North. Children of the 1920s, they are the first generation born in the newly created Northern Ireland, and the religious split in this age group demonstrates the demographics that underpinned partition.

Now look at the population in Northern Ireland, from the same census, of children under five. There are 147,000 under-fives, and this age group is 48 per cent Catholic and 37 per cent Protestant.

So, between the births of these two groups, 90 years apart, the Catholic population of children, as a percentage of the total, has nearly doubled while the Protestant population has practically halved.

Every politician needs to be aware of these facts when considering Brexit and the future relationships on this island. They help us to forecast the political future of the North using numbers rather than opinions or slogans. (For the sake of transparency, let me declare that my Protestant family in Belfast were split down the middle, half voting for Brexit, the other half to remain. Christmas dinner at the in-laws’ should be interesting.)

Extrapolating from these figures, I calculate that Catholics will become the absolute majority in Northern Ireland around 2036, and this majority will only strengthen from then on. That’s less than 20 years away. The Belfast Agreement was signed 20 years ago, and it seems like only yesterday.

What does all this mean? It means changes are coming, and coming quickly. Could Coveney be right about a united Ireland? Maybe.

But could the Republic absorb the North economically? To answer this, we have to understand that the two economies are very different. The union with Britain has been an economic calamity for Northern Ireland. All the people have suffered, Catholic and Protestant, unionist and nationalist.

In 1920, 80 per cent of the industrial output of the entire island came from the three counties around Belfast. Belfast was the biggest city in Ireland in 1911, larger than Dublin, and was home to Ireland’s innovation and technology.

At partition, the North was industrial and rich, the South agricultural and poor. Fast-forward to now, and the contrast couldn’t be greater. The collapse of the Northern Ireland economy compared with that of the Republic has been unprecedented. East and West Germany come to mind.

Economically, the Union has enfeebled the North while independence has enriched the South – particularly since the peace process. Commercially, there was a huge peace dividend, but it went south.

The Republic’s economy is four times larger, generated by a work force that is only two and a half times bigger. The Republic’s industrial output is today 10 times that of the North. Exports from the Republic are 17 times greater than those from Northern Ireland, and average income per head in the Republic, at €39,873, dwarfs the €23,700 across the Border.

Immigration is a traditional indicator of economic vitality. In the Republic, one in six people are immigrants, the corresponding figure for the North is one in a hundred.

Dublin is three times bigger than Belfast, far more cosmopolitan, and home to hundreds of international companies.

It would still be a huge challenge to the Republic’s economy to absorb the North – and many Southerners mightn’t want to if asked.

The differences aren’t just economic; they are cultural, not only in the sense of flags and commemorations but also socio-culturally.

And this is where the TripAdvisor index comes in, revealing that the North is another country in a different sense. Take Kilkenny and Armagh, a similar-sized Northern town with city status. TripAdvisor has reviews of 176 restaurants in Kilkenny but of just 43 in Armagh. The entry for Coleraine has only 58, for Antrim just 49.

This tells its own story of small-business activity, how we socialise, how we spend money, and how society is structured. The North is different. Demographics are leading to a changed North, but Coveney’s dream of a united Ireland might not be the end point. Some Northern Catholics may want to remain in the Union, which ironically could be more attractive if the Catholic population were in the majority, because they’d have the power without having to pay for it.

Also, many people in the Republic might baulk at the unification bill. But the demographic patterns pose the most significant and immediate challenge for unionism, because, within a generation, democratic politics in the North will come down to whether unionism can persuade nationalism to keep Northern Ireland intact.

Now that is a tall order.

Subscribe

Here is an even more meaningful indicator of matters in common to all on this island I daresay ; . . FOR HOMOSEXUAL KICKS + SATANISM + STATE-CRAFT + GEO-POLITICS IT DEMONSTRATES : NORTH + SOUTH Collusion IRISH STATE + NORTH EAST OF IRELAND + BRITAIN Collusion CATHOLIC & PROTESTANT LITTLE BOYS RAPED & MIND-CONDITIONED BY : BRITISH ROYALS ; incl. Earl Lord Mountbatten [ Founder of CIA, Last Vice Roy of India, Admiral of the UK Navy Fleet, & so much more Sir Anthony Blunt ; 1/2 Brother of the King of England, The 5th Man [ 6th Man… Read more »

Who in their right mind would want to it on – the two tribes can never integrate. The unionist side being descendants of border reevers, who were by nature semi-feral, will always remain ghettoised. Even those who upped and left northern Ireland for the US in previous centuries ended up running ahead of authority and hiding out in the Appalachian Mountains. Marching on the 12th there, they became known by a distinctive name.

Then there’s the KKK connection – it goes on and on, all equates to trouble

I believe this is the fifth or sixth time his drum has been banged. With all this brexit, you’d think he might have something else to write about.

Hardly statistically robust. Why do Protestants live into their nineties more often than Catholics? They do, actually.

Who emigrates?

Catholic immigrants such as Portuguese and poles are included with indigenous Catholics.

The north was richer for the first 70 years. That’s ignored for some reason.

Most importantly, the Irish Catholic is heading towards overall minority status on an all island basis.

There’s a new world coming and this is yesterday’s row.

I believe this is the fifth or sixth time his drum has been banged. With all this brexit, you’d think he might have something else to write about.

Hardly statistically robust. Why do Protestants live into their nineties more often than Catholics? They do, actually.

Who emigrates?

Catholic immigrants such as Portuguese and poles are included with indigenous Catholics.

The north was richer for the first 70 years. That’s ignored for some reason.

Most importantly, the Irish Catholic is heading towards overall minority status on an all island basis.

There’s a new world coming.

And that’s twice I’ve banged that drum. If anyone knows how to delete a post, please do it.

And that’s it? With all the dramatic events that are taking place in the north of Ireland right now – I mean Brexit, DUP, hard-border, single market, the regulatory alignment, and all other legal, economic, political and geopolitical issues resulting from the collapse of the May-Varadkar talks last night – that’s all that the Author and the venerable Commentators have to say about this week’s political developments in the North?! I thought that I’ll find out from yous what the nearest legal future of NI (and the future of both Ms May and Conservative-DUP coalition) will be :-( – with… Read more »

Last year I was back in Malmo, Sweden, a short visit, having been a regular visitor to the city in the early 90’s, and I had to keep reminding myself that the Malmo city of my memory was indeed the one and same place, am I in Islamabad or Malmo? The transformation was beyond, well, words. One people had replaced another people. Muslims. Malmo Muslims, who I believe are now the city’s majority population, who according to my Swedish old friends, never integrate, have disdain for Swedish culture and law, and feel themselves to be superior to the native infidel… Read more »

More border stuff.

Referring to more than the headline victim.

Hetero-male aspect no doubt.

Females likely involved as facilitators with governance of institutions

And, the high ranking homosexual orgy network — without boys … hmm ! — involving very senior politicians stretches all the way deep down South.

Upon such gatherings is State-Craft — Irish State + NEOI vis-a-vis Britain & EU & NATO practised.

.

.

https://villagemagazine.ie/index.php/2017/11/boiling-over/

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FoU8bffZSsQ

“Hard” Border or “Soft” Border for “Irish State”-“North East of Ireland” is still going to involve a ramping up of Orwellian State in both jurisdictions.

.

Yee have been very foolish to not put a stop to Photo ID Card forced upon Irish Citizens.

.

With that Stazi Photo ID Card system + associated database, yee will BE snookered + FEEL snookered from showing any dissent about anything worth having dissension for.

FBi is being revealed as biased and not objective. Stinking corruption protected Clintons and witchhunt on Trump.

http://www.foxnews.com/opinion/2017/12/05/gregg-jarrett-how-fbi-official-with-political-agenda-corrupted-both-mueller-and-comey-investigations.html

http://www.kitco.com/news/2017-12-03/Venezuela-to-Launch-Cryptocurrency-To-Fight-Blockade-Maduro.html

This is a redrafting of several previous articles with Tripadvisor being bolted on top. For Ulster Presbytrians this is a rather trouble predicament that they face. They only know themselves as being number 1. The psychological adaptation is going to be severe. They are focussed on the wrong stuff. Cars, bread&circuses, TV, jobs that have been eliminated by offshoring, the Old Testament, white bread and jam, burgers and fries, and working hard in what is a welfare statelet. Plus all the military stuff. And that is the thin end of the wedge towards societal decline. To be honest, having a… Read more »

Regarding the Tripadvisor count…maybe this is an honest reflection that Northerners eat so much junk food. Generally, the food gets better the further south you go. Swedish meatballs ? No thanks. Not if I was starving. Give me spagetti Bolognese any day. And give me Spanish ahead of German food. Even within countries it gets better as one goes south. In France Lyon surpasses Paris. And in Ireland Kinsale surpasses anything in Dublin, for quality – at the same price, despite the scale advantages of Dublin. More restaurants, and better restaurants as you had south – implies the inverse. Northerners… Read more »

Dear Mr McWilliams. The myriad tribes of these islands cannot allow #Brexit to dominate & derail the neccessary ongoing upcycling of the factional identities which contest and claim dominion over both the British and Irish Meta-Narratives. Such work is the essential pre-cursor for any plausible convening of a ‘United Ireland’ at any future stage. The residual elements of previous eras who pledged allegiance to fundamentalist iterations of their tribal identities cannot be allowed to use the Brexit process as a way of re-establishing their toxicity in younger generations. This applies to any and all identity affiliations on both sides of… Read more »

Christine Keeler of “The Profumo Affair” died today aged 75 years. . Reckon that The Profumo Affair was manufactured as a scandal so as to protect Victor Rothschild for having stolen the Nuke secrets to give to USSR & Izzy. . North East of Ireland & the rest of Ireland was very much the playground for the long-running & constant homosexual abuse of boys shenanigans under spy-master Victor’s control ; Thankfully, Victor not a homosexual pedophile himself or so it seems ; He into women only. . Reminding once again ; It is with such gatherings that future of Ireland… Read more »

Concerning demographics, there are SIX North Western counties in a state of irreversible demographic collapse.

Donegal, Leitrim, Sligo, Mayo, Cavan, Roscommon.

Much of Galway, and Tipperary is no better.

And that demographic problem is much worse than any in the North East of the island.

No mention of it.

I don’t think people care about a united Ireland. Many could not have cared less for quite a long time now while those who did cannot see the point any more because Ireland, even in the guise of Modern Ireland, has gone for good. When did this happen? My guess is some time during the last two years, but don’t take my word for it. Thinking about it, a passage by John Waters (“Was It For This?”) came to mind. “… A society does not have a continuous personality in a way that human beings tend to have: rather it… Read more »

Finally, after decades of fruitless research, a missing link between a monkey and a human has been found – a Tory MP Bernard Jenkin, or Jerk-in – for friends, Jerk:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pMQzIGR8eqo

And my summary of Mr Jerk-in:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k5ba1OKY7Xc&t=0m45s

David has asked what if Gerry Adams is a top plant / spy for the British Intelligence Service.

.

And, so how about this ?

.

.

https://www.henrymakow.com/001399.html

F for Fake ; Semantically speaking

.

Artificial Intelligence for Fake ; Factually speaking

.

.

https://www.bibliotecapleyades.net/ciencia2/ciencia_artificialhumans109.htm

Concerning the obsession with the superficial, and belief…..nothing is more ridiculous than the outcry in the Middle East, over what is effectively obvious. Jerusalem was founded by the Jews. And it is the political capital of Israel. Trump is stating the obvious. And of course Trump has spent his life with New York’s Jewish business community. He effectively sees the Jewish perspective very well. He is also a pragmatist. He r than most. For a certain belief system, which is tied to symbolism, and facade, there is a need to maintain the agressive illusion that it’s purpose is to conquer,… Read more »

Re ; The Religion that u dare not speak its name . Even the last part — “This is also reflected on it’s relentless demands of supression of female emotion.” — signifies that it is Judaism u speak of. . Well, this would be so were one not to know of Hitchens bias for his own ethnic background & bias against the latest religion to begin in the Middle East. . So, no, it is Islam that u speak of. I too have my misgivings about aspects of Islam. But, I assure u that true Judaism is even more severe… Read more »

@ Grzegorz, I mentioned this great BBC drama series to u before ; . “The Detective” . The lead character Police Commander Crocker is an English man of Polish heritage ; A fact which the viewer is often reminded of with occasional deep interest he indulges into his family tree. Even his wife remarks upon this habitual practise of his. . Also, that angle — SEXUAL LICENTIOUSNESS [ e.g.s orgies & pedophilia ( But, “Deviance” the more fitting category name for the latter ) ] that I am emphasizing is at play in Irish State-North East of Ireland-Scotland-England+Wales & EU… Read more »

Google results for Search String ;

.

.

The Detective AND BBC 1985 AND Tom Bell

.

.

https://www.google.com/search?q=The+Detective+AND+BBC+1985+AND+Tom+Bell&dcr=0&ei=6GspWoHkEsat0ATUnLnYBg&start=0&sa=N&biw=1301&bih=633

Tripadvisor index – Kilkenny 176 restaurants to Armagh 43 Restaurants. Immigration index – Rep of Irl 1 to 6 ratio , NI 1 to 100 ratio. Average wage index – Rep of Irl 39,873e , NI 23,700e. Health Care Index Nurse/bed ratio as per oecd report – Ireland. 4.5 nurses to 1 bed UK. 2.9 nurses to 1 bed Spain. 1.7 nurses to 1 bed France 1.5 nurses to 1 bed Tonight on RTE Dr Andy Jordan tells us that us that if every GP in the country identified 10 patients for the Cross Border Healthcare Directive 30,000 patients would… Read more »

Spain spend 2100 euro per capita

Ireland spend 3800 euro per capita

on health care.

Ireland and their im alright JACK public sector unions expect NI , France and Spain to be their healthcare subcontractors.

Put it on the national debt tab .

Resources are measureable in any snapshot of time.

Soft/hard border for Ulster throws spanner in the negotiations between UK and EU

https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2017/dec/04/juncker-and-may-fail-to-reach-brexit-deal-amid-dup-doubts-over-irish-border

Whatever deal is special for NI gets a me too echo from Scotland and London/southeast.

“NAZIs” WERE IN ALLIANCE WITH “ZIONISTs” IN WW2 ANYWAY ;

.

.

Henry Makow? @HenryMakow

.

HEADING ;

Jewesss Chelsea Handler, Who Calls Trump A Nazi, Finds Out Her Grandfather Was Actual Nazi

.

10:15 am – 9 Dec 2017

.

.

https://twitter.com/HenryMakow/status/939559169006321664

HERE IS A SCOOP ON ANTI-IRISH NATIONALISM JOURNALIST Kevin Myers / “Kevin My-Arse”

[ Ref. The Phoenix satire magazine’s nickname for him ]

.

.

HEADING ;

Acclaimed journalist Kevin Myers on how ultra-Zionist hate groups destroyed his career

.

.

The Ritchie Allen Show

.

.

Dec 7, 2017

.

.

http://www.thetruthseeker.co.uk/?p=162437

“And speaking of Russia (where contrary to Russian propaganda for the useful idiots in the West, Islam – and not Christianity – is the main religion), I guess you’ve missed that bit of news too: it is now ILLEGAL in Russia to conduct Bible studies at homes, and the Russian police and their so-called courts are PERSECUTING people who gather at their OWN homes to read the Bible, or hand it out – the so-called “Yarovaya package” which forbids Bible studies outside the State-controlled (read: FSB/KGB controlled) buildings.” This caught my eye Grzegorz I googled religion in modern Russia. What… Read more »

David finally talking about Crypto-Currencies / Cyber-Currencies

.

.

HEADING ;

David McWilliams on four very expensive words:

‘This time it’s different’

Bitcoin and financial markets are rising disturbingly fast.

Let’s not forget our history

.

.

https://www.irishtimes.com/opinion/david-mcwilliams-on-four-very-expensive-words-this-time-it-s-different-1.3319540?mode=sample&auth-failed=1&pw-origin=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.irishtimes.com%2Fopinion%2Fdavid-mcwilliams-on-four-very-expensive-words-this-time-it-s-different-1.3319540

DNA Studies Results for all of Ireland with reference to :

Scotland

England

Wales

France

Norway

Spain

inter alia

5 acres with a horse and a cow may be your near future and you will be thankful..

https://srsroccoreport.com/u-s-economic-crisis-ahead-major-failure-of-analysts-to-spot-danger/

@ Grzegorz, Apropos of ur report that ; . [ Deep State of Russia > Dugin > ] Putin has already recognised Jerusalem as Israel’s capital in April 2017 . . Are they trying to f..k with our heads with this ; . EXCERPT ; “…The United States’ recognition of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital “defies common sense,” Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov said Friday. . Russian President Vladimir Putin said Thursday he was “deeply concerned” by Washington’s decision to recognize Jerusalem. … ” . . https://www.timesofisrael.com/russia-says-trumps-jerusalem-declaration-defies-common-sense/?utm_source=dlvr.it&utm_medium=twitter . . ALSO, HERE IS 1 OF THE “PUBLIC-RELATED” REACTIONS : . . https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/1.827864… Read more »

“Whether the biblical passages are an history account or a prophecy depends on when the narrative was written. Remember it is all written by the hand of man. Politics rule. Follow the money. Two adages worth remembering. “I envy you that you are probably enjoying a Polish-like dry, snowy winter – Met Eireann has been predicting heavy snow, but all we got was a f…g rain all night (it has been very dark all day – like at early dawn! – so much so that I have to have a light on in the kitchen – so maybe that indicates… Read more »

If I forget thee, O Jerusalem, let my right hand forget her cunning.

This is a powerful scene that I hope you will enjoy:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yTdHDVeeXYE

Would Irish State facilitate North East of Ireland [ NEOI ] similarly ?

.

.

https://twitter.com/HenryMakow/status/940340064802017280

Poland … pole-axed ?

.

.

https://twitter.com/thetolerantman/status/940175799201796096

@ Grzegorz,

.

.

EWE MAY WELL BE RIGHT WITH UR THESIS AS TO THE SELF-CHOSENITES GOING CHRISTIANMany a true sentiment is said in jest ;

.

.

From “Beth Midler” no less

.

8-)

.

.

https://twitter.com/BetteMidler/status/940259422370070528

.

…………………………………………………..

.

And, note that Beth Midler hosts this reply too ;

.

.

https://twitter.com/4seasonspix/status/940510524558553088

.

This is what Irish State-North East of Ireland-Britain[-EU-NATO ] round table discussions was really negotiating 8-) [ “FINE-TUNING” ] ; . . THEIR VERSION OF ; . . http://www.bbc.com/news/av/world-asia-china-42248056/in-your-face-china-s-all-seeing-state . . I TOLD YEE SOME MONTHS AGO THAT “THE PHOTO ID CARD + ASSOCIATED DATABASE CONSPIRACY OF IRISH STATE” IS THE MOST IMPORTANT + SINISTER ISSUE HAPPENING NOW AGAINST THE IRISH CITIZENS. AND, IT WILL ALSO BE OPERATING ON BOTH CATHOLICS & Our Grumpy Theologian Brethren IN North East of Ireland [ NEOI ] ; Certainly every time they interact with the Border. ANYWAY, I TRUST THAT BRITS HAVE ALL… Read more »

This website is visually attractive ;

It has some useful info.

But, in my very brief perusal I discover that some hyper-links do not work ;

Perhaps this will be remedied.

Anyway, here is a Time-Line which includes mention of :

earliest known inhabitants of Ireland

Darwinism claims for origin of human beings ;

Thus, contrary to the Bible ;

Nathanyahoo’s super slim bible even.

A bible which hints of being Luddite

vis.

No Gospels

Within this website the frequent dangers that lurk in public swimming pools in Netherlands inter alia is highlighted

https://isgp-studies.com/world-history-in-timelines

A treatise on how to regain individual sovereignty.

“The main tool used against We the People, is the fiat currency in nations around the world. These instruments of debt are the main source of power and control by TriEvil. If we move with one unified message – Hacking at the Root – we can take back our sovereignty and regain our freedom.”

https://thedailycoin.org/2017/12/12/taking-back-our-sovereignty-and-hacking-at-the-root-of-trievil/

Apropos of

1_

example of currency which may become de-facto currency during Ireland Unification Period

2_

David’s next article

https://www.reuters.com/article/us-markets-bitcoin-risks-insight/bitcoin-fever-exposes-crypto-market-frailties-idUSKBN1E7254

http://blogs.reuters.com/felix-salmon/2011/12/16/why-payments-wont-ever-be-anonymous/

@ Grzegorz,

Cozy Shop “Irish State” AND Cozy Shop “North East of Ireland [ NEOI ]”

both

conduct

the

following

Orwellian Tactics

which

this

Politician [ Dail Eireann TD ( Labour Party ) ]

is

highlighting

about

the

Garda-Landlords / Landlord-Gardai

.

.

http://www.irishexaminer.com/ireland/alan-kelly-queries-if-gardai-bugged-phone-464431.html

I am cynical about Trump even before he got elected / put into office as President ;

And, he has no affinity for Ireland.

But, his mother did.

Still, the following is something to be very thankful for because of the Trump phenomenon ;

THE TWEET ;

Henry Makow?

@HenryMakow

Whatever Trump really represents, his election can be compared to turning over a rock and seeing the slugs in gov’t, media and law, liberals who have subverted the nation, scurry in a frenzy.

https://twitter.com/HenryMakow/status/941035800862617600

Again, … on-topic & interesting ;

http://www.orwellianireland.com/

Truthist,

Just trying to tease out the transfer scenarios for the Basic Income economic model.

Everyone would have to contribute 8 hrs public sector duty.

4 million would recieve 74bn ( approx 18,000e each basic income/ safety needs income) + public sector housing.

Would 18,000e become the median income?

People could work for improved houses, education, holidays and cars .

There would still be inequality.

The person that wants to work, pay a mortgage, not smoke, drink less and look after their health probably should be unequal.

People should be helped.

Not sure about equal.