What is the true state of the housing market in Ireland and what does it mean for you? There’s a huge amount of hype, speculation and sales talk doing the rounds and in this cacophony and noise, it is hard to get a true picture. One way to look at the property market is through the eyes of two very different generations of Irish people.

The first generation is the people who bought at or close to the top of the market. For these people, price increases of late are only meaningful if prices keep rising so that they can get out of negative equity.

The second group is the investors – or, as they have been referred to lately, the ‘cash buyers’. For them, the pivotal issue is the yield on the property.

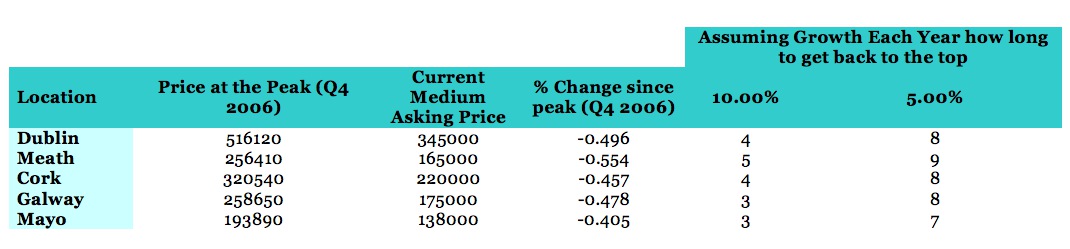

This week there was loads of data published about the property market and it gives us the opportunity to deliver a snapshot about where it is right now. In order to make some sense of the numbers for both groups, I have taken the rental data published yesterday by daft.ie and the house price data published, also yesterday, by myhome.ie. In table 1, I have calculated how long it will take for my first generation to get out of negative equity.

If property prices rise – as they have in Dublin over the past year, by 10pc – it will take four more years for them to get out of negative equity. However, if prices were to rise by a more modest 5pc per year, it would take another eight years. In the more likely scenario of a 5pc price rise across the board, people in Meath will not be out of negative equity until 2023. This is shocking.

These are the young families I wrote about here many years back, in 2006 to be precise. They were the ‘juggling generation’, juggling childcare, community and massive mortgages – they are going to be juggling for some time to come.

At the other end of the scale is the ‘cash buyer’ or the investor. These are mainly older people and these investors are playing a huge part, yet again, in the Irish property market.

Why is this?

It is because when you hear the favoured description these days of the ‘cash buyer’, this person is almost always an investor. By investor I mean that this is a person who already has a house and is buying a second place to rent.

The strange aspect about the ‘cash buyer’ is that they are elbowing out the first-time buyer or the second-time buyer. Talk to anyone in an urban part of Ireland who is in their thirties and wants to move to a slightly bigger house, they will tell you that they are being outbid by older buyers, typically in their fifties or sixties. So what is happening? What is the dynamic?

Years ago I referred in this column that there was a generation of ‘accidental millionaires’ – people who bought their houses in the 1980s and early 1990s – whose house values had risen so much that they were sitting on a goldmine without the mortgage. Fast forward seven years and they are today’s cash buyers. They may have traded down in the boom, made a few quid and have no debt.

BECAUSE they don’t have to borrow, they are already at a 5pc advantage over the young family that has to borrow from the banks at 5pc interest.

Therefore, what counts for them is the prospect of further rises in prices and the yield that the rent of the house gives them. Remember, they are getting close to 0pc on their deposits so whatever the house is yielding is greater than the amount they are getting in the bank.

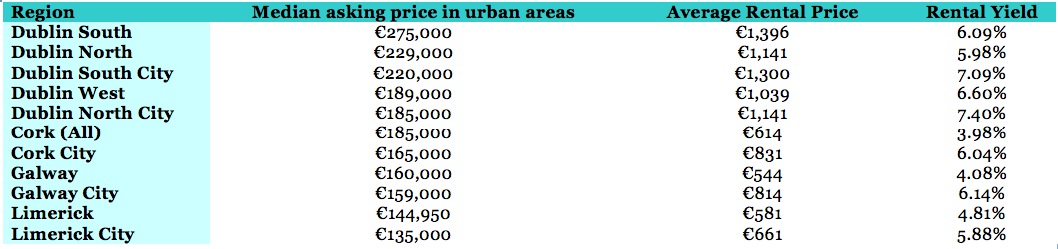

So let’s look at the yield the cash buyer is now getting. I figure this out by taking the average price of a house in Ireland. I then calculate how much rent the house gets a month and multiply this by 11 months.

The reason we don’t take 12 months is because there is always a risk that the property won’t be rented all the time. Then I calculate what that annual rent is as a percentage of the original price of this house. This gives us the dividend, or the annual return, to the investment.

Taking the Daft.ie data published yesterday, we see some very interesting trends. Now these figures are crucial to the cash buyers, or the part-time investor, who has always been a presence in the Irish housing market. Look at table 2 to see all these figures.

We see some strange anomalies. Although houses in south Dublin are far more expensive – €90,000 on average – than houses in Cork, they are better value.

This is because rents are much higher and much firmer in south Dublin than in Cork. In fact, Cork is the most expensive place for the cash buyer in Ireland. In contrast, north inner city Dublin is the best value of all the urban centres because whereas prices have fallen there, rents have remained strong.

This is because Dublin city is still a place that is growing and living in the city, whether it is northside or southside, is still living in the centre of a thriving city.

The story of the Irish property market as it unfolds is the story of two very different generations – one very lucky; one very unlucky.

Who would have thought that your financial prospects in a country could have been dictated by such an arbitrary factor as the year you were born?

David McWilliams writes daily on international economics and finance at www.globalmacro360.com

Subscribe to receive my news and articles direct to your inbox

Thanks David, Great detailed explanation of the luckies and the unluckies.

I am curious about the new kids aroound the block – the youngest generation in their late teens and early twenties – freshly out of the leaving cert, new graduates. What are the options for them? Can the new graduates get employment and earn enough salary so that they can leave the nest? Or are they leaving the country to find employment elsewhere with financing from parents? Would they have enough to pay their monthly bills? Or are they the new hidden homeless, continuously “in between jobs”, moving from one poky room to the other. It will be a serious… Read more »

Ah so it’s to do with the year one is born, and there was me thinking it was down to misguided policies and reckless mismanagement of banking systems that was to blame ..sheesh! Just bad luck I guess :(

Subscribe.

‘Who would have thought that your financial prospects in a country could have been dictated by such an arbitrary factor as the year you were born?’…..

Or…..’Who would have thought that your financial prospects in a country could have been dictated by such an arbitrary factor as the family you were born into?’

Or…’Who would have thought blah blah

Move along..Nothing new here!

I am confused, sorry, not an economist but like reading David’s blog. On the negative equity – the suggestion is that if house prices keep going in Dublin then people who bought at the peak (like us in 2005) will be out of NE in 10 years or so. But surely these people (me) have been paying off their mortgage for the last 10 years and so what they owe now is obviously a lot less. We always figured we were ‘stuck’ because of negative equity but seeing what houses are selling for on our street now we reckon with… Read more »

David, Good point but negative or positive equity is irrelevant if you live in the house and are making the repayments. You might feel poorer/richer but only if you have to crystalise a loss is it a real issue. You may be paying more to live in the house than you would have to have done if you bought later, but interest costs are now lower so affordability is better. You might check your math though. Prices have not fallen as far below peak as you show. Dublin is 33.1% down on your figures, it may then need a 49.6%… Read more »

Hi, A very good follow up on the previous article on commercial property. Two points though; The massive foreign reits are squeezing out more people than older cash buyers. Also your info on prices was from daft which are only asking prices. If you took the data from the site which registers actual sale values your yields will be a lot higher and property values lower. Factor in the fact that sale prices are waaaaaaaaaaaay below production costs means no new supply for a loooooooooooooooong time increasing upwards pressure on rents. Government policies are only making the problems worse charging… Read more »

Good article, I think though that something obvious is missing in this analysis. We have been through 6 years and more, of a recession that has obliterated wealth, which has left most people I know (I work in the private sector), pretty much without a brass pot to piss into. Savings have been nuked, incomes have been slashed, yet one special part of our national congregation have managed to largely insulate themselves from this, and are now perfectly positioned to buy property on the cheap… Up and down the country, we are hearing stories of people in their 50’s and… Read more »

Extremely good point DarraghD!!

A sobering article from Constantin Gurdgievin in Sunday Times Business looked beyond the official unemployment figures. He calculates the true unemployment figure to be double the official one, that our real youth unemployment figure is on par with Spain/Greece, and that of all the unemployed 2/3’s are long term. His fear, as no country can sustain such a huge drag on its economy for long, without drastic employment generation, is the country risks both social/economic meltdown. With this in mind one may ask what’s driving up house prices? David nails it. Speculators. Like London, it’s a speculation bubble facilitated by… Read more »

One bit that always seems missing in this analysis is that the money the boomers have right now will eventually be inherited. Admittedly some people, my parents included, are trying to spend as much as they can, but those houses are not going any where, they can’t migrate. OK now that said, does that money get inherited by the struggling negative equity generation and even if it does will it happen in a timely enough manner to help them or will their opportunities and the lives they are trying to provide to their children have passed by. I am aware… Read more »

There’s a whole bunch of things wrong with this analysis. The rental yield in general in Dublin is nothing like 6% or 7%. It’s true for houses in place like Crumlin where the prices aren’t completely insane but the rents are as high as elsewhere. Even at 7%, when you factor in 50%+ income tax, house and (new) water tax, insurance, maintenance, and either property management charges or your own time spend on being a landlord (plus a mountain of hassle) … the net returns of a couple of per cent simply aren’t worth it compared to sticking the money… Read more »

WHY IS DUBLIN CITY COUNCIL BUYING UTILITY HOUSES IN DRIMNAGH BECAUSE IT IS CHEAPER THAN BUILDING, PAY RENT 160 EUROS MONTHLY AND THE NEIGHBOURS PAYING MORTGAGES OF OVER A GRAND+ YOU COULDNT MAKE THIS UP

Re your Global Macro 360 article: “Now that inflation is well below target, why doesn’t it cut rates?” Why is it an accepted tenet of economics that low interest rates and increased money supply is the only way to create demand and thus inflation? Economists need to understand that the problem is not a reluctance to loosen but what happens to the money when it is loosened. You believe David that “some liquidity scheme to help the banks” would “compel banks to lend”. Would that it were true. And there lies the problem. You need to come up with a… Read more »

In the aftermath of the IMF bailout, I was told that the banks (then under state [ taxpayer] ownership, had a to prioritise their allocation of mortgage credit. The top priority – to establish a base under the Dublin residential property market – which was of systemic importance to the entire banking system. Yes, folks – every factor influencing the state of the real estate market in Dublin/the east region had to be upheld at all costs. Think about that !!! The search for suckers never ended. The crunch will come with respect to property tax. Watch as politicians in… Read more »

and in the news – the Saudis declare me now as “a terrorist!”

Release the withheld 28pages and we’ll see who the terrorist really is !!! What a cover up !!! more lies !!!

http://lmgtfy.com/?q=http%3A%2F%2Flibertyblitzkrieg.com%2F2014%2F04%2F01%2Fsaudi-arabia-passes-new-law-that-declares-atheists-terrorists%2F

this Michael Krieger has often actually something worthwhile to say!maybe check him out…

28pages,

The last couple of weeks we are getting to a stage that comments are closely related to the topic. You may have a point but be honest, do you think this is somewhat over the top?

Latest bombshell, is NAMA’s sale of it’s NI proprty portfolio.

The effective loss to the PAYE taxpayer exceeds 75%.Sold to a US private equity firm. All gone in one lump. No effort to find buyers for individual properties.

Somethings stinks about this.

0% haircut for the bondholders.

75% haircut for the PAYE taxpayers.

National debt spiralling out of control.

MoF is another clown. Just as useless as Lenihan.