If coronavirus eventually recedes as we all hope, public health will be gradually elbowed out by public housing as the number one issue facing our economy.

A year ago this week, an election was fought more or less on the issue of housing. Sinn Féin did exceptionally well in that ballot, not least because it created the perception that it cared more than others about the anxieties of younger people.

Fianna Fáil once put council houses at the centre of successive manifestos and the party that fixes today’s housing problem will be rewarded, possibly by generations of voters. Fairly priced accommodation relative to income is the policy that has the potential to really change people’s lives for the better. To achieve an outcome that will enrich the everyday experience of millions, the entire country must buy into a different way of looking at housing.

In successful economies such as Germany, housing tends to be regarded as a cost rather than an asset. This means that the thrust of policy is towards fair housing costs, without an implicit bias towards upward house prices.

Low accommodation costs are good for the economy; they make sure that wages can remain competitive and that people can live and work in the same neighbourhood without having to commute miles to find affordable homes. Putting “fair” housing costs at the centre of policy is socially, environmentally and economically sensible.

For example, when rents start rising in the German capital, the Berlin authorities impose rent controls. This sends a clear signal to everyone that the State will not tolerate rents that rise far above income – such rents serve only to enrich landowners while penalising everyone else.

Rent controls are a blunt instrument, but they make it explicit that the State regards accommodation as a cost and – like the costs of electricity, food or clothing – the bias must be towards value for the many, not excessive profits for the few. If wealthy Berliners want to spend fortunes on their apartments, they are welcome to do so, but for the average person, that state has declared, “we have your back”.

The Germans start with income – people’s wages – as the foundational price in the economy and work backwards from there.

Contrast this with Ireland. Here, we start with the price of houses as the foundational price and work around that.

We construct all sorts of wheezes to maintain this lunacy, irrespective of the reality of people’s incomes. We engineer help-to-buy schemes, shared-equity arrangements, first-time buyers’ grants, various interest rate products, 30-year mortgages, and buy-now-pay-later options.

All of these are designed to put people into long-term debt and short-term penury, in order to validate already inflated house prices. The implicit message is: “Don’t worry we’ll keep prices up, so you can eventually sell on to a greater fool and trouser the capital gain.”

Housing Affordability

The problem is that the greater fool is your children and their children.

The result is that, even in this pandemic, house prices in Ireland continue to rise, between 5 and 7 per cent throughout the country, despite the fact that unemployment has risen, businesses are boarded up and commercial rents are falling.

There is a solution to this silliness. Our entire nation has been bullied into starting the conversation with house prices and working hard to validate existing prices, but we are getting things back to front.

Imagine abandoning the notion that the house price is regarded as totemic and everyone must worship at its feet? What about starting with income?

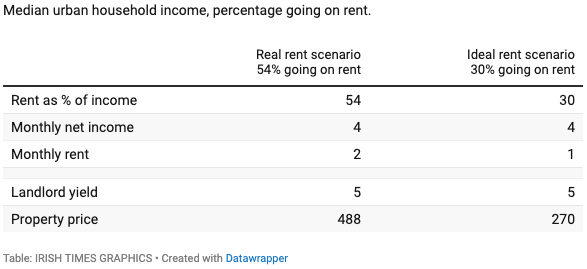

Let’s construct a little economic model of house prices and where those prices could be if we used wages rather than house prices as the starting point. It is generally accepted that rents of around 30 per cent of after-tax income are fair. Rents are the income that accrues to the property owner and should determine the value of the asset.

Let’s see how much people ought to be paying based on Irish wages.

The median family’s after-tax income in Ireland €3,750 per month. This means such a family should be paying rent of around €1,125 per month. In order to put a value on the asset and a fair price on the house for a landlord, let’s assume (very generously) that a landlord needs a 5 per cent yield to remain in the business.

At a 5 per cent yield, the house should be worth the annual rent (€1,124 multiplied by 12, or €13,488. If €13,488 constitutes 5 per cent of the price, then the total value would be €270,000 as the fair price of a home in Ireland.

Coincidentally, this €270,000 for a new family home is still above the prices that O’Cualann Cooperative has successfully built and sold homes for in Dublin, Waterford and Cork the past two years. This can all be done.

Remember, this model gives a yield of 5 per cent to landlords which is far in excess of what they should be getting in a world of 0 per cent interest rates.

You can play around with the numbers yourself. This model shows you that if we use people’s wages as the foundational price in the country (which is precisely what we should do), house prices would fall significantly.

At the moment, around the county people are paying on average 38 per cent of their income on rent, while this rises to 54 per cent of income in Dublin.

Could we provide homes at these fair prices as other countries do? Of course, we could.

But the private building sector won’t do this on its own. It needs to be coaxed with the offer of long-term revenue streams rather than short-term profit windfalls.

The State must lead, providing development land that it already owns at a deep discount and waiving VAT. The State should drive hard bargains with builders to drive the cost of 21st-century council houses down to €290,000. Kick-ass quantity surveyors, representing the taxpayer, should be able to get value for money. Builders who want to engage with this scheme could apply to tender.

The State could choose to own all the houses and could secure an annual yield of 5 per cent. To build these houses, it would raise money on the bond market, which it can do at close to zero per cent. With these borrowings it could fund, say, 500,000 homes at these prices over 10 years.

There would be a significant profit for the State, as much as €5,000 per year per home profit (around 2.5 per cent). Over 10 years, that would end up being €2.5 billion per year. And this could be reinvested in the housing stock, meaning we would never have a housing problem again.

Rich people would of course still be free to buy expensive houses, but this mechanism allows the State to put a cap on the price of homes for working families. The future of accommodation in a sophisticated economy would revolve around using income as the foundational price and working from there, plus deploying the power of the bond market to finance everything.

Welcome to the 21st century, post-Covid.

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me.

I don’t think the title of your article matches the content lol. Just kidding, mainly because I had some doubts after reading the article. https://www.binance.info/ru/join?ref=YY80CKRN